By Ratan Bhattacharjee

Ratan Bhattacharjee on Ukrainian poets who have risen against the Russian invasion.

“My subject is war and the pity of war and the poetry is in the pity,” wrote Wilfred Owen nearly a hundred years ago. Today, the same picture of devastation is being witnessed by poets all over the world who sing the pity of war.

“My subject is war and the pity of war and the poetry is in the pity,” wrote Wilfred Owen nearly a hundred years ago. Today, the same picture of devastation is being witnessed by poets all over the world who sing the pity of war.

In Ballad of Bawling Babies, a poem on the Russia-Ukraine war, portal reporter Mekhala Saram wrote: “Valour is mute/ So if war comes/ It will not be the sound of honour/ Of sturdy men in/ sturdy boots/ That you will hear/ What you will hear/ However/ Will be a ballad of bawling babies/ Broken, Ailing, Hungry.”

Margaret Atwood, Salman Rushdie and Tsitsi Dangarembga are among more than 1,000 writers from around the world who have condemned Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in an open letter by PEN International saying there “can be no free and safe Europe without a free and independent Ukraine”.

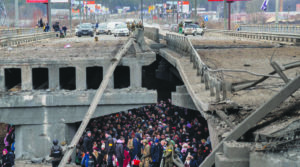

Poets in Ukraine, too, have raised their voices against the war. The devastating impact of war becomes evident all over their country where men and women are fighting Russian bombs with Molotov cocktails and stones.

Audrey Kurkov, the president of PEN Ukraine from Kyiv is constantly inspiring his countrymen with a video that says: “This is my city, my home, my country, my native land… I will never welcome occupiers.”

After the war began, the renowned satirical writer said he “didn’t feel ready to laugh at anything.” Since the has been a large part of the modern Ukrainian literary canon since 2014, many writers of Ukraine are weaving tales of bravery and heartbreak for children to recite in school.

After the war began, the renowned satirical writer said he “didn’t feel ready to laugh at anything.” Since the has been a large part of the modern Ukrainian literary canon since 2014, many writers of Ukraine are weaving tales of bravery and heartbreak for children to recite in school.

The works of poets of yore such as Taras Shevchenko and Ivan Franko are also being recited. The people hope that the world in future will appreciate the anti-war poetry of Ukraine.

Many are now of the opinion that Russian President Vladimir Putin has chosen the wrong country to mess with. Once a poet from Putin’s own country wrote: “Whoever is making a jam in Russia/ knows there is no way out.”

Today in Ukraine, when the soldiers are chasing the civilians, poets and writers, all are busy finding a way out not only with Molotov cocktails and stones but also with poetry or novel to draw the attention of the world.

Former Ukraine President Victor Yanukovych was rejected for trying to lean toward Putin. We lived happily during the war, a poem published in Poetry International in 2013, read: “When they bombed other people’s houses/ we protested/ but not enough, we opposed them but not/ enough.”

Former US President George Bush’s bombing of Baghdad is not much different from Putin’s bombing of Kyiv. Both are invasions and both used false premises. Even the threat of nuclear weapons is so dastardly uttered each moment. Odessa is bombarded. But we all know that most of the Odessa people are Russian speakers. Putin is sending troops to bomb Russian speakers who have nothing more than Molotov cocktails and stones to throw at the Russians. The Ukrainians knew how their grandfathers fought the German tanks on tractors. They are taking this war with Putin like a movie or a poem. But it is real and Ukraine this time is devastated.

The way in which Ukrainian poets have risen against Russian aggression is outstanding. On the first day of March when Russian planes were bombing fiercely from the sky over Ukraine, poets and writers organised a Zoom poetry reading on land.

The way in which Ukrainian poets have risen against Russian aggression is outstanding. On the first day of March when Russian planes were bombing fiercely from the sky over Ukraine, poets and writers organised a Zoom poetry reading on land.

People taking to poetry in a time of crisis is nothing new. It is the poet who can inspire the nation. We saw such poetic endeavours during our freedom movement.

A journalist made this appeal in the newspaper: “The Putins come and go. If you want to help, send us some poems and essays. We are putting together a literary magazine.” This togetherness is inspired by poetry. Poetry unites, war divides.

Ukrainian literature, which had developed under prolonged foreign domination over its soil — including those of the Romanian and the Ottoman empires — was given a fillip by the Soviet dissidents during the post-Stalinist or post-totalitarian phase of Communism. In 1991, it broke free from the shackles of the censorship era and its tradition of social realism. The increased freedom and openness brought about a marked change in the landscape of Ukrainian literature; it moved away from the shadows of Soviet and classical periods and emerged into an era in which writers had the freedom to write about issues that were forbidden in Soviet Ukraine.

Ukraine is paying the highest price for democracy and poetry is needed for inspiring the people amid the full-scale Russian invasion.

What is more, poets have stepped up and now they are making important contributions to the war effort by volunteering or taking up arms. One such poet is Oleg Sentsov who was arrested on trumped-up terrorism charges for protesting the Russian annexation of his native Crimea.

He spent five years in a Russian penal colony and pushed himself to the brink of death during a hunger strike that lasted 145 days. Since his return to Ukraine in a prisoner exchange in 2019, he has been artistically thriving and his satirical alien invasion novel ‘The Second One’ is a thinly-veiled allegory of a Russia-Ukraine war published in 2020. His film ‘Rhino’ also was premiered before this latest escalation.

Stanislav Aseyev, a poet-journalist of Ukraine also wrote after his arrest: “I just don’t have time to be afraid or cry and I see that thousands of Ukrainians feel that way too.” Aseyev wrote about the ongoing war crimes in Donbas by Russia in his book The Torture Camp on Paradise. Explosions keep him waking at night in Kyiv. Artem Chapeye is another Ukrainian author who took up arms against Putin’s forces. He is a four-time finalist of the BBC Ukraine Book of the Year Award, the most prestigious prize in the Ukrainian literary world. The self-proclaimed pacifist poet said, “There is so much human suffering. I know we’ll win, but at what cost?”

(Ratan Bhattacharjee, a senior academician and trilingual poet and columnist)