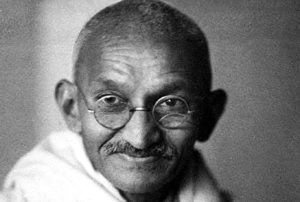

Mohandas Karamchand “Mahatma” Gandhi remains, even 75 years after his assassination, a useful symbol for many in India. For secularists, the leader of the country’s independence movement represents an imagined India of the past. For the current government, he is a means by which it can soften its international image.

In his 2002 essay, academic Ashis Nandy, mentioned four versions of Gandhi, who led India’s move from British colony to independent nation.

In his 2002 essay, academic Ashis Nandy, mentioned four versions of Gandhi, who led India’s move from British colony to independent nation.

The first is the Gandhi of the Indian state and of official Indian nationalism. The second is a puritanical and sombre figure, apolitical and dependent on state funding, the subject of university seminars debating: “What would Gandhi do?”

The third is the “Gandhi of the ragamuffins”, opposing mechanisation, large-scale development and a high-consumption economy. The fourth is Gandhi the non-violent revolutionary, a worldwide phenomenon, influential in movements but no longer feared by tyrants, nor taken seriously by the left.

Over the past two decades, however, Gandhi and his legacy have taken a thorough beating.

Reappraisals of Gandhi are, admittedly, long overdue. Titles such as “Mahatma” (“high souled” or “venerable” in Sanskrit) and “Father of the Nation” have worn thin since his death, as new events in India and worldwide that brought new scrutiny to his life, work and politics.

Some of these seem far-fetched, for example equating Gandhi with Osama bin Laden and global jihadists on the grounds that they were similarly based on a “sacrificial humanitarianism”. Speculations about his sexuality provoked a debate about his supposed “celibacy”. In the aftermath of the #MeToo movement, his strange practice of sleeping next to naked young women was openly discussed.

The rise of much-persecuted Dalit people (previously known as untouchables) in political and intellectual spaces over the past two decades has given rise to trenchant criticisms of Gandhi’s complicity in the preservation of caste dominance, and the hypocrisy in his stands repeatedly that favoured the preservation of caste over justice and emancipation. Economist and politician Bhimrao Ramji “Babasaheb” Ambedkar’s evisceration of Gandhi’s politics is now more widely known and accepted than ever before.

The rise of much-persecuted Dalit people (previously known as untouchables) in political and intellectual spaces over the past two decades has given rise to trenchant criticisms of Gandhi’s complicity in the preservation of caste dominance, and the hypocrisy in his stands repeatedly that favoured the preservation of caste over justice and emancipation. Economist and politician Bhimrao Ramji “Babasaheb” Ambedkar’s evisceration of Gandhi’s politics is now more widely known and accepted than ever before.

Of those images of Gandhi named in the essay, some are now seen as enemies of the vision of progress of India’s current prime minister, Narendra Modi. Others have been refined to sit comfortably within the cultural nationalism of Hindutva, the project of creating a constitutional Hindu state and institutionalising its version of Hindu culture and social order in contradiction to Gandhi’s vision of a multi-faith nation.

Those using Gandhi’s methods of protest are now likely to be labelled “urban Naxal”, a Hindutva shorthand for intellectuals and activists involved in struggles of the rural poor, and have draconian legal charges slapped on them.

Gandhi’s international influence and reputation is now much diminished. Gandhi’s use of racist words for black Africans has fuelled righteous outrage against him.

Malawi’s government stopped construction of a Gandhi statue after these accusations, though pressure from Modi’s government resulted in the completion of the statue later.

In Ghana, Gandhi’s statue was pulled down. Black Lives Matter movements in the US and in the UK also branded him a racist, and called for removal of his statues.

How Modi uses Gandhi

The most far-reaching bid to move India away from the nation that Gandhi imagined has come from India’s ruling Bharatiya Janata party (BJP) and its parent organisation, the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). The RSS was briefly banned after Gandhi’s killing for its involvement in the crime. It espouses a violent communal polarisation with an anti-minority politics, and several episodes of mob lynching with impunity, have been the fertile ground for its rise.

While Gandhi emphasised truth, fake news has been has been used to mobilise mass support for Hindutva. The RSS also tries to quote Gandhi in support of their political approach.

However, Hindutva organisations organise tableaux annually to re-enact the assassination on January 30 1948. Those elements of the RSS who supported “Gandhian socialism” are in political hibernation.

Modi, the Hindutva state and the new official nationalism, though, still need Gandhi. Under Modi’s modernisation fetish, major Gandhian ashrams, like Sabarmati, have been given such a tourist-friendly facelift, seemingly stripped of all historical gravitas.

Modi launched his Swachh Bharat [or Clean India] campaign using Gandhi as the logo. Home minister Amit Shah claims that Modi is Gandhi’s true modern manifestation.

Modi supports the construction of Gandhi statues worldwide. At the UN, Modi said he represented the land of Gandhi, claiming that erecting a bust at the UN headquarters was a matter or pride for all Indians.

Modi’s Gandhian paradox is that the only Gandhi he wants to assimilate into his project is a Gandhi shorn of his core beliefs, principles and modes of political action.

Is the influence of Gandhi’s ideals finished then? Not quite. Activists from the anti-Citizenship Amendment Act movement (an attempt by Modi to end Muslims’ constitutional equality with Hindus) claimed to be follow Gandhian principles of popular protest. The farmers’ movement against Modi’s plans to give corporations power over Indian agriculture also tried to mobilise Gandhi’s legacy to their cause.

Perhaps, with the benefit of hindsight, there is a clearer picture now of the man, stripped of much of the myth and mystique. A resource for many social movements forging alternative ways to meet contemporary challenges.

(The Conversation)