As Senator Robert F Kennedy on April 4, 1968 uttered these words from the scribbled notes made in his car during his campaign trail, he announced one of the most shocking news in the racial conflict ridden modern history of the United States.

His words were met with screams and shock from the crowd as he went on to inform about the killing of King by a white man: “Martin Luther King dedicated his life to love and justice for his fellow human beings, and he died because of that effort. In this difficult day, in this difficult time for the United States, it is perhaps well to ask what kind of a nation we are and what direction we want to move in.”

“I had a member of my family killed, but he [assassinated US president John F Kennedy] was killed by a white man. But we have to make an effort in the United States, we have to make an effort to understand, to go beyond these rather difficult times.”

Some 55 years later as I walked inside the National Center for Civil and Human Rights museum in Atlanta, I almost relieved the time the United States witnessed over centuries. The day after Robert F Kennedy’s speech, the New York Times headline read: Martin Luther King Is Slain in Memphis; A White Is Suspected; Johnson Urges Calm

“The Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., who preached nonviolence and racial brotherhood, was fatally shot here last night by a distant gunman who raced away and escaped. Four thousand National Guard troops were ordered into Memphis by Gov. Buford Ellington after the 39-year-old Nobel Prize-winning civil rights leader died. A curfew was imposed on the shocked city of 550,000 inhabitants, 40 per cent of whom are Negro,” it reported.

Living in a polarised world riven by racial and religious hatred, the experience at the

National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta calms you down. You are suddenly reminded the words of Spanish-American philosopher George Santayana – “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.”

The National Center for Civil and Human Rights inspires visitors to pause and reflect, to be tolerant. The immersive exhibitions, dynamic events and conversations, and engagement and education/training programme make this place very special.

The 42,000 square-foot center is designed by architect Phil Freelon who created a physical representation of its vision. The curved walls of the Center represent two cupped hands, protecting something sacred: the dignity of all human beings.

The exterior façade displays many tones, a mosaic of different nationalities that represents the idea that people from all walks of life can work together in harmony.

You begin the tour on a corridor with two sides labelled in neon showing the “White” and “Colored” worlds of Atlanta in the 1950s.

The Center’s iconic exhibitions feature the papers and artifacts of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.; the history of the civil rights movement in the United States; and stories from the struggle for human rights around the world today.

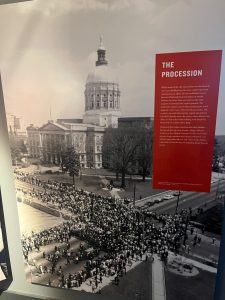

In this museum, the gallery titled The March On Washington (one of the most iconic moments of the US Civil Rights Movement) captured my attention. The gallery is a multimedia experience that highlights the events of the day when King gave his seminar speech- “I Have A Dream”.

The March was designed to put pressure on the federal government to enact civil rights legislation, protect civil rights, and improve working conditions for African Americans.

You can hear the exciting sounds of protests and songs, and learn more about key players in the event’s successful planning and execution.

The March on Washington immediately became associated with Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I Have a Dream” speech. According to the museum website, there was a great deal more to the story that day.

Inside the museum I learnt about the infamous Jim Crow laws of the United States. They were state and local laws introduced in the Southern United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries that enforced racial segregation. “Jim Crow” is a pejorative term for an African American. Creating a society based on white supremacy, the law separated people of colour from whites in schools, housing, jobs, and public gathering places. Such laws remained in force until 1965.

“A Legacy of Creative Protest: King & Youth Activism” at the museum demonstrates how a generation of youth activists, inspired by Dr. King’s rally for equality, helped to transform political landscapes from the Civil Rights era to present-day through innovative means of protest.

The gallery titled Freedom Riders took me on a tragic ride to May 14, 1961 when near Anniston, Alabama, a bus carrying Freedom Riders ( groups of white and black activists who participated in bus trips through the American South in 1961 to protest segregated bus terminals) was firebombed. While there were many Freedom Rides prior to this one, the exhibit focuses on this particular tragic event.

Visitors enter a reconstruction of the same Greyhound Bus that Freedom Riders rode that day and are immersed by oral histories from the Riders, as well as a short film inside of the bus.

The National Center for Civil and Human Rights is a reminder to all even these days about how freedom is not given but won through a long struggle and sacrifices of people. It believes in justice and dignity for all – and the power of people to make this real.