Indian director Sanjay Leela Bhansali is known for his big-budget Bollywood production, featuring grand sets, star casts, meticulously choreographed dance sequences and lavish costumes, jewellery and furnishings. His new series for Netflix, Heeramandi: The Diamond Bazaar, lives up to these expectations.

Indian director Sanjay Leela Bhansali is known for his big-budget Bollywood production, featuring grand sets, star casts, meticulously choreographed dance sequences and lavish costumes, jewellery and furnishings. His new series for Netflix, Heeramandi: The Diamond Bazaar, lives up to these expectations.

Against this visually rich backdrop emerge the scheming, menacing and murderous courtesans of Heeramandi.

The series is set in Heeramandi, a historical red-light district of Lahore in present-day Pakistan. It unfolds against the backdrop of the Indian freedom struggle against British rule.

The show is an entanglement of plot lines – a murder investigation, a war of succession, a budding love story and a courtesan’s secret involvement in a rebellion against British rule.

The show is an entanglement of plot lines – a murder investigation, a war of succession, a budding love story and a courtesan’s secret involvement in a rebellion against British rule.

Eventually, all characters and storylines converge around the central theme of anti-colonial nationalism. Driven by nationalist fervour, the courtesans call themselves “patriots” and willingly sacrifice their careers and lives for the country.

But who were the real courtesans?

Role models for female independence

The show takes creative liberties by distorting the lives and timelines of the historical courtesans.

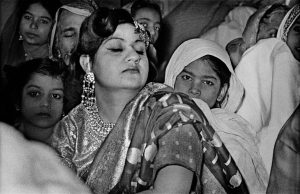

The North Indian tawa’ifs (courtesans), or nautch-girls (dancing girls, as the British called them), were cultural idols, female intellectuals and entrepreneurs.

Dating back to ancient India, these women were trained in music, dance, fashion, poetry, repartee, etiquette, languages and literature from a young age. Typically following a system of matrilineal inheritance, courtesans passed down their professional knowledge and skills to talented daughters of the household.

Dating back to ancient India, these women were trained in music, dance, fashion, poetry, repartee, etiquette, languages and literature from a young age. Typically following a system of matrilineal inheritance, courtesans passed down their professional knowledge and skills to talented daughters of the household.

Once trained, courtesans attracted patronage from royal courts, feudal aristocrats and colonial officers.

This unique class enjoyed privileges not afforded to most women in Indian society, such as education and personal income. They led glamorous lifestyles, wielded power and wealth, and paid taxes.

As independent professionals, they contributed to Indian arts and culture, travelled extensively, made connections with chosen kin and often embraced gender fluidity.

Their financial, political and sexual independence challenged patriarchal gender norms and restrictive Hindu moral laws that dictated the lives of women from upper-middle-class families.

Complicated relationships

In Heeramandi, the courtesans turn patriotic to avenge the British police officers for raping and killing the natives. While these actions are dramatic, the historical relationship between courtesans, the British empire and Indian nationalism was more complex.

The politically engaged Bibbojaan (Aditi Rao Hydari) mirrors Azizan Bai, a courtesan from Kanpur who is said to have financially supported the 1857 mutiny against the British East India Company.

While the mutiny was one of the most widespread anti-colonial revolts of the 19th century, Indian nationalism was not its primary aim, but a consequence. Azizan’s interest was in maintaining her patronage from the native rulers for her social and economic wellbeing.

After 1857, India’s governance shifted from the East India Company to the Crown, leading to the spread of British rule across India alongside Western education and Victorian morality. Meanwhile, nationalist leaders envisioned a nation as a pure land of sacred Hindu ancestors and valued chastity in women.

Both the imperial and nationalist ideals clashed with the courtesans’ sexual freedom.

In the 1890s, Hindu reformers and bourgeois nationalists joined Christian missionaries in organising anti-nautch campaigns that advocated boycotting them to “rescue” art and culture from perceived immorality. This led to the downfall of the courtesan class.

In Heeramandi, patronage diminishes and the women’s dreams of marriage fade. The courtesans shut down their salons, give up their careers and sacrifice their lives for the nation.

But historical courtesans were quick to reinvent themselves in the face of declining patronage and social stigma.

They turned to the power of modern technology. Gauhar Jaan, a famous courtesan, became a celebrated concert singer and gramophone artist, earning the title of “India’s Melba” in the international press.

In 1921, Gandhi asked Gauhar Jaan to perform for the Swaraj Fund. Aware of the ambiguous position courtesans held in nationalist discourse, she agreed on the condition that Gandhi attend her performance. When Gandhi failed to show up, she contributed only half of the raised amount to the cause.

Courtesans contributed significantly to the founding of the Indian film industry through their artistry, star power and capital investment. The first generation of female film stars came from courtesan backgrounds: Jaddan Bai, Kajjan Bai, Akhtaribai Faizabadi and Naseem Banu entered the industry as actors, singers, composers, directors and studio owners.

Later, some acted as managers and costume designers for their daughters, the emerging actors of the next generation.

By becoming modern-day artists, the courtesans preserved their art. They remained visible and relevant in a society that was increasingly obliterating women’s cultural contributions and diminishing their role as citizens in an emerging nation.

Patriarchal nationalism

In the show, a woman’s value is judged by her respectability, marital status and the presence of a male guardian controlling her sexuality. Courtesans refer to themselves as “birds in gilded cages” and dream of freedom from their courtesan lifestyle.

Here, the courtesans’ nationalism resonates with present-day far-right Hindu nationalists, seemingly promising women empowerment in nationalism but, in reality, reserving only regressive roles for women.

Heeramandi oversimplifies the multilayered persona of tawa’ifs. The series portrays them as melancholic victims yearning for patriarchal married bliss, while remaining marginalised in respectable society. But these women should be remembered as celebrated figures filled with joie-de-vivre, gusto and spiritedness.

They should be honoured for their strategies of self-representation and processes of self-determination, as they turned resilience into a way of life. (The Conversation)