Jnanendra Das elaborates on the convergence of East and West on the spooky night of Halloween, making a case for bridging cultures.

The Eastern world of ghosts meets the West this year making it truly the spookiest night. This October 31 brings a rare convergence in the world of the supernatural. Across continents, the Western celebration of Halloween and the Bengali festival of Bhoot Chaturdashi fall on the same night, creating a unique cross-cultural moment where traditions honouring the dead overlap in an eerie harmony. Both rooted in ancient customs, these two festivals remind us of a common thread in human culture—the desire to connect with those who have passed on and seek protection from unseen forces.

The Eastern world of ghosts meets the West this year making it truly the spookiest night. This October 31 brings a rare convergence in the world of the supernatural. Across continents, the Western celebration of Halloween and the Bengali festival of Bhoot Chaturdashi fall on the same night, creating a unique cross-cultural moment where traditions honouring the dead overlap in an eerie harmony. Both rooted in ancient customs, these two festivals remind us of a common thread in human culture—the desire to connect with those who have passed on and seek protection from unseen forces.

A Night of Spirits

Halloween has its roots in the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain, a three-day fire festival celebrated in present-day Ireland, Scotland, and parts of Northern Europe. It marked the end of the harvest season and the onset of winter, symbolising a transition to the darker half of the year. The Celts believed that on this night, the barrier between the living and the dead was at its thinnest, allowing spirits to cross over into the mortal world.

Halloween has its roots in the ancient Celtic festival of Samhain, a three-day fire festival celebrated in present-day Ireland, Scotland, and parts of Northern Europe. It marked the end of the harvest season and the onset of winter, symbolising a transition to the darker half of the year. The Celts believed that on this night, the barrier between the living and the dead was at its thinnest, allowing spirits to cross over into the mortal world.

To honour the dead and invite the spirits of their loved ones, they held feasts, performed rituals, and sacrificed crops and animals. To protect themselves from malevolent entities, they donned costumes and masks to disguise themselves and lit bonfires to ward off the darkness. They also carved lanterns from hollowed-out gourds—a tradition that eventually evolved into the modern jack-o’-lantern.

To honour the dead and invite the spirits of their loved ones, they held feasts, performed rituals, and sacrificed crops and animals. To protect themselves from malevolent entities, they donned costumes and masks to disguise themselves and lit bonfires to ward off the darkness. They also carved lanterns from hollowed-out gourds—a tradition that eventually evolved into the modern jack-o’-lantern.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the globe, the people of Bengal in India commemorate Bhoot Chaturdashi, also known as Narak Chaturdashi, a night steeped in tradition and  folklore. This marks the Fourteenth day of Krishna Paksha (the second fortnight of a lunar month) in Kartik (The eighth month of the Hindu calendar). Since it is just one day before the new moon, the night is comparatively dark.

folklore. This marks the Fourteenth day of Krishna Paksha (the second fortnight of a lunar month) in Kartik (The eighth month of the Hindu calendar). Since it is just one day before the new moon, the night is comparatively dark.

On this night, the spirits of 14 forefathers are believed to return to visit their living descendants. To honour and guide these ancestral spirits, homes are adorned with 14 earthen lamps, illuminating the night to protect against unwanted entities and guide the friendly spirits.

Lighting Darkness

Though separated by geography, the symbolism of light connects these two traditions. In Halloween celebrations, jack-o’-lanterns—initially carved from turnips and later from pumpkins—are placed outside homes. These glowing faces are not just for fun; they have roots in the belief that the light would protect homes from wandering spirits.

Though separated by geography, the symbolism of light connects these two traditions. In Halloween celebrations, jack-o’-lanterns—initially carved from turnips and later from pumpkins—are placed outside homes. These glowing faces are not just for fun; they have roots in the belief that the light would protect homes from wandering spirits.

Similarly, on Bhoot Chaturdashi, the lighting of 14 lamps is a central tradition. These lamps are placed throughout the house, especially near entrances, windows and dark spots to act as a beacon for the spirits of ancestors and as a barrier against evil forces.

The Thin Veil between Two Worlds

At the heart of both Halloween and Bhoot Chaturdashi lies the belief in a thin veil between the worlds of the living and the dead. Halloween’s origins are steeped in the idea that on October 31, the spirits of the deceased roam the earth. This belief is echoed in Bhoot Chaturdashi, where it is said that ancestors return to visit their living relatives.

At the heart of both Halloween and Bhoot Chaturdashi lies the belief in a thin veil between the worlds of the living and the dead. Halloween’s origins are steeped in the idea that on October 31, the spirits of the deceased roam the earth. This belief is echoed in Bhoot Chaturdashi, where it is said that ancestors return to visit their living relatives.

This shared notion serves as a reminder that across cultures and continents, the mystery of death and the desire to honour those who have passed remain universal. The two festivals, while distinct, are bound by the common human need to remember, honour, and protect.

Similarities of Differences

While children in the West don costumes, go trick-or-treating and there are haunted houses too. Many families and TV Stations even make a horror movie marathon. In Bengal, there are ghost stories that get the centre light. While Vampires and werewolves, the zombies, and Bloody Mary spend chills down the spine on Halloween night, ghosts in Bengal’s Bhoot Chaturdashi folklore are known for their mischievous traits and uncanny quirks.

While children in the West don costumes, go trick-or-treating and there are haunted houses too. Many families and TV Stations even make a horror movie marathon. In Bengal, there are ghost stories that get the centre light. While Vampires and werewolves, the zombies, and Bloody Mary spend chills down the spine on Halloween night, ghosts in Bengal’s Bhoot Chaturdashi folklore are known for their mischievous traits and uncanny quirks.

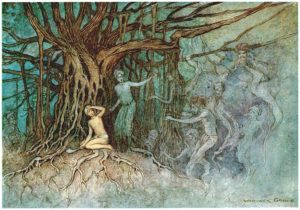

For example, Shakchunni is the spirit of a married woman who dons traditional shell bangles (Shankha) and haunts other married women to assume their identities. Petni are  female ghosts who died with unfulfilled desires or were unmarried, while the Besho Bhoot resides in bamboo groves, causing harm to those who cross fallen bamboo. The fish-loving Mechho Bhoot demands fish from people and threatens them if denied and the Gechho Bhoot are tree-dwelling spirits. The most famous of them all in Grandma’s tale is the Brahmodaittyo, a benevolent spirit of a holy Brahmin, depicted as kind and helpful to the living.

female ghosts who died with unfulfilled desires or were unmarried, while the Besho Bhoot resides in bamboo groves, causing harm to those who cross fallen bamboo. The fish-loving Mechho Bhoot demands fish from people and threatens them if denied and the Gechho Bhoot are tree-dwelling spirits. The most famous of them all in Grandma’s tale is the Brahmodaittyo, a benevolent spirit of a holy Brahmin, depicted as kind and helpful to the living.

In this rare moment where both worlds collide, the world seems to come together in a shared belief that life and death are intertwined and that even in the darkest times, the lights we carry—whether in pumpkins or earthen lamps—keep us connected to our roots  and guide us forward.

and guide us forward.