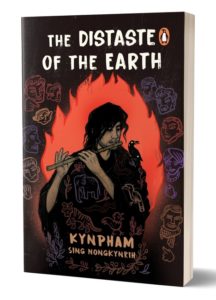

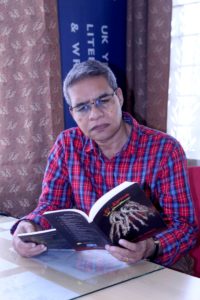

Acclaimed Khasi writer, Prof. (Dr) Kynpham Sing Nongkynrih (KSN) shares his journey from penning poetic love letters in high school to becoming an influential voice in Indian literature. 2024 Shakti Bhatt Literary Prize awardee, Nongkynrih opens up about the evolution of his craft and the cultural richness of Khasi folklore. Known for his evocative poetry, drama, and prose, he discusses his latest novel, The Distaste of the Earth, and other works. Through humour, humility, and a profound love for his roots, Nongkynrih offers insights into the writing process in an interview with Sunday Shillong (SS). Excerpts from the interview are as follows:

Acclaimed Khasi writer, Prof. (Dr) Kynpham Sing Nongkynrih (KSN) shares his journey from penning poetic love letters in high school to becoming an influential voice in Indian literature. 2024 Shakti Bhatt Literary Prize awardee, Nongkynrih opens up about the evolution of his craft and the cultural richness of Khasi folklore. Known for his evocative poetry, drama, and prose, he discusses his latest novel, The Distaste of the Earth, and other works. Through humour, humility, and a profound love for his roots, Nongkynrih offers insights into the writing process in an interview with Sunday Shillong (SS). Excerpts from the interview are as follows:

SS: Congratulations on winning the Shakti Bhatt Literary Prize! How do you feel about receiving this honour?

KSN: To be chosen for such a national award from among so many renowned writers is a profoundly fulfilling experience. I feel truly humbled and honoured.

KSN: To be chosen for such a national award from among so many renowned writers is a profoundly fulfilling experience. I feel truly humbled and honoured.

The honour is sweeter for the reason that the distinguished writers at the Shakti Bhatt Foundation do their own research and selection. I’m even more delighted because this award is also a recognition of Khasi literature, which is part of my body of work.

SS: So how did the journey begin? Were you always into literature and writing even when in school?

KSN: I unknowingly started as a poet, writing hundreds of love letters to hundreds of girls in high school. Only much later, when I reread them, did I realise they were quite poetic.

The letters were never for me; I wrote them for my friends, who offered me tea money for my services.

The letters were never for me; I wrote them for my friends, who offered me tea money for my services.

My own poem came much later after my matriculation when I fell in love with ‘a divorcee, a woman old enough to be my aunt’. But that is a story for another time.

SS: When did you first get published?

KSN: After my first poem addressed to my first love, I wrote numerous others in Khasi and English, carefully preserved in my diaries. Some of them finally saw the light of day years later when Jayanta Mahapatra published them in The Telegraph’s Sunday Magazine.

My first two poetry books, Moments and The Sieve, were self-published with Writers Workshop in 1992. Later, I determined not to pay for publication and didn’t submit any more manuscripts. I chose instead to publish my poems in journals and magazines.

My first two poetry books, Moments and The Sieve, were self-published with Writers Workshop in 1992. Later, I determined not to pay for publication and didn’t submit any more manuscripts. I chose instead to publish my poems in journals and magazines.

And then, the Kovalam Literature Festival happened in 2008. By a quirk of fate, I shared the stage with literary icons like Satchidanandan and Shashi Tharoor. After I read my poems, Karthika, then the publisher at HarperCollins, approached me, saying, “I must publish your poems!” I was stunned. It was rare to be approached by a publisher like that! That was how I became a HarperCollins writer.

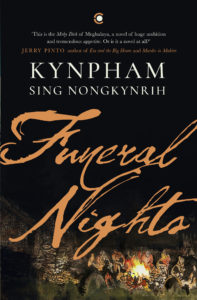

Among the poems I read was ‘Blasphemous Lines for Mother’, with a line saying, “those days in Cherra,” referring to my childhood in Sohra (Cherrapunjee). Karthika, intrigued, suggested I write a memoir. Instead, I promised her a genre-defying work—something big and bold—which led to my epic-length novel, Funeral Nights. That marked my debut as a novelist!

Among the poems I read was ‘Blasphemous Lines for Mother’, with a line saying, “those days in Cherra,” referring to my childhood in Sohra (Cherrapunjee). Karthika, intrigued, suggested I write a memoir. Instead, I promised her a genre-defying work—something big and bold—which led to my epic-length novel, Funeral Nights. That marked my debut as a novelist!

SS: The Distaste of the Earth is a novel inspired by Khasi folklore. What drew you to the story and fictionalise this narrative?

KSN: I was captivated by the tragic love story of Manik Raitong and Lieng Makaw, a tale that could be described as The Queen and the Pauper. I wrote a short story about it, included in Around the Hearth: Khasi Legends. Reader reactions inspired me to explore the story further, creating a play and later a novel that explores existential themes about earthly powers and godly dispensation, delving into the depths of love, loss, and the human-non-human relationship.

SS: Lyngkien’s “pata” becomes a focal point in the novel. What role do you feel these social spaces play in the narrative?

KSN: The microcosm of the local bar facilitates the vivid portrayal of provincial life and adds depth and authenticity to the narrative.

In the past, the pata or the local bar was a gathering place of people and, hence, a storehouse of knowledge and information. Patas are now frowned upon, but in the book, it was chiefly through the characters who frequented the local pata that people learnt about the tragic event unfolding in their capital town.

SS: What role does literature play in preserving and evolving cultural narratives?

KSN: Literature is vital in preserving and evolving cultural narratives, making the past new and relevant to the present. The present must have a symbiotic relationship with the past and draw its strength and guidance from it as it journeys into an uncertain future.

SS: With an extensive body of work spanning poetry, drama, and fiction, which genre do you feel allows you to most effectively express your voice?

KSN: I’m first and foremost, a poet. I don’t feel happy or complete if I don’t write poetry. Poetry is like ‘an upwelling of hot spring’: its emanation is unstoppable. The novel is like the river of life, ‘constantly surging, / constantly in flood’. Once you put yourself in its path, there is no turning back.

SS: Can we talk about your upcoming projects, such as Lapbah: Stories from the Northeast?

KSN: Lapbah: Stories from the Northeast, co-edited with Dr Rimi Nath, is an extensive anthology featuring some of the best short stories from the eight North Eastern states, both translated and originally written in English. Penguin will publish it in two volumes next February.

SS: How do you approach blending traditional Khasi narratives with modern themes?

KSN: I believe that every Khasi myth carries the wisdom of the race and that every legend speaks with symbolic overtones. My method is to select traditional narratives that are metaphorical in this way.

In The Distaste of the Earth, for instance, I talk about the world of Manik, where man is a despot, and God is ostensibly absent. This world is much like our own today, especially if we keep in mind conflicts and mass killings like the hellish, live-streamed genocide in Gaza.

SS: You often explore power dynamics, human greed, and the environment. How do you decide on which themes to emphasise in your writing?

KSN: These themes are inextricably intertwined. If you talk about the one, you have to talk about the other. Need and greed, for instance, are mostly responsible for many of our ecological crises. But more than need, greed, as taught in Khasi thought, is the mother of all evils.

SS: How does Meghalaya influence your literary voice?

KSN: My writing is deeply rooted in the land, my people’s culture, the times, and especially, the past—a repository of knowledge. Yet, being rooted doesn’t mean being parochial. Rootedness can lead to transcendence.

SS: Who are some of your greatest literary influences, and how have they shaped your work?

KSN: Some of the most inspiring poets for me are Neruda, Nicolás Guillén, Derek Walcott, Tudor Arghezi, Giorgos Seferis, Czeslaw Milosz, Adam Zagajewski, Wisława Szymborska, Miklós Radnóti and Jaroslav Seifert. There are also South West Asian poets like Mahmoud Darwish, Adonis and Yehuda Amichai. I also admire classical Greek and Roman poetry, classical Chinese poetry and the Japanese haiku masters.

My debut novel was influenced by Boccaccio’s The Decameron, Plato’s Socratic Dialogues, The Arabian Nights and Gao Xingjian’s Soul Mountain. I have an eclectic taste in books.

SS: With your experience as an educator and mentor, what advice would you give to emerging writers?

KSN: Write what you know best and what you are most passionate about. Read widely and intensively: it expands the mind and hones both creative and critical faculties. Above all, keep writing and seek guidance from honest critics—flatterers are your worst enemies.

(Interviewed by Jnanendra Das)