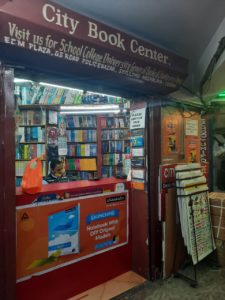

Shillong’s book depots, once a thriving business, are at a crossroads today. Thanks to declining reading habit as also online shopping facility. Premier bookstalls like Modern Book Depot, Chapala Book Stall, Ratna’s Mascot, Kamala Book Agency, Assam Book Depot are long gone or are facing uncertain future.

Stuck between classics preferred by the aging and audiobooks chosen by the multi-tasking young, several stalls have converted to cafés, while others have chosen to shut shop.

With declining readership, the city’s bookshelves have been gathering dust.

Those book stalls which are still able to keep themselves afloat, are also weathering the impact of pandemic.

Sujit Singh, 47, owner of National Book Agency at Khyndai Lad, says, “Our sales had started declining way before the pandemic’s onset. Most of our regular customers belong to the older age group, who prefer to read classics and non-fiction.”

Singh says some youngsters, who anyway visit the stall rarely, only ask for fiction by authors such as Chetan Bhagat and Ravinder Singh.

On bestsellers, he says, “We have been selling several copies of books such as Asura: Tale of the Vanquished, a novel by author Anand Neelakantan, and Around the Hearth by Kynpham Sing Nongkynrih.”

Singh says, “We do sell Khasi and Hindi books, but they do not sell much.”

Sellers look for alternatives

One of the oldest book agencies in Shillong, Ka Ibadasuk (formerly called Ratna’s Mascot), has now turned into a café.

Ernesterwill Kharmamlong had bought Ratna’s Mascot in 1991and changed its name to Ibadasuk after his youngest daughter.

Ernesterwill’s 32-year-old daughter, Balarina Kharmamlong, who runs Pa’s Café at Khyndai Lad, says, “We realised that Khyndai Lad did not have a café that serves Khasi food exclusively. We turned the Ka Ibadasuk Book Agency into a café about four years ago after we started incurring huge losses. We now sell Khasi food and we are doing well.”

“After online shopping websites such as Amazon and Flipkart took over and began offering 50% to 60% discounts on books, people started looking for cheaper options and we could not match up. In fact, I would myself look for books online,” she says.

“Our agency used to sell fiction and non-fiction by Indian and foreign authors and we used to supply books across the region. The fall in readership affected us beyond redemption as we did not sell textbooks to balance out our losses. We tried several ways to revive the book culture, but to no avail. Moreover, Kindle and audiobooks were increasingly growing popular,” she says.

Another retailer, Binayak, who owns a bookshop at Keating Road, says he has started selling stationary after the pandemic.

“Even the sale of textbooks has fallen. I had to turn to stationary to make ends meet,” he says.

Singh says he is a third-generation bookseller. He says while the store his father set up had to be shut and his family continues to own two stores at present.

Bookstores such as Modern Book Depot at Khyndai Lad and Akashi Book Depot that were popular in the 90’s, were forced to shut shop years ago.

Effects of pandemic on buyers

Stores which sell textbooks and guidebooks, however, still manage to make a profit. Textbook-sellers have been hit hard by the coronavirus pandemic. “Our sales have fallen by 60%. Schools haven’t been operating and many people have lost their jobs. Parents are not buying all the required textbooks and many children rely on online study material these days,” says Yusuf, owner of Sahil Book Depot on Keating Road.

Madan Prasad, who works at Nicholaus Book Shop, says, “We keep all kinds of books in English and Khasi. People hardly buy novels these days.”

“The pandemic has affected consumer behaviour. Even college-goers do not buy textbooks anymore. They prefer to look up topics on the Internet or buy just notes,” says Prasad.

Spiritual, character-building top lists

Buddhadeb Chaudhuri, owner of Chapala Book Stall on Keating Road, says, “We sell books in English and Bengali. Our buyers are 50 years old or more and they prefer reading religious texts, mythology and non-fiction. A few women do look for thrillers and mysteries.”

Sister Helena, manager at Pauline Book Store at Laitumkhrah, says, they specialise in spiritual, psychospiritual and self-help books in English, Khasi and Hindi.

“People from all age groups and all walks of life come to our store,” she says.

“We have sold several copies of the psychospiritual book Man’s Search for Meaning by Viktor E Frankl. It is our bestseller for the month,” she says.

As the bookstore has ample book stands and shelves, students from nearby schools visit the store regularly.

“Children love to read the character-building books available here,” she says.

Young adults of the 20-35 age group constantly look for self-help books, she says.

The price range of self-help books at the centre starts at Rs 150, while that of religious texts begins at Rs 200.

“We send books to libraries across the region. We also organise book fairs in June and September and offer books at a discounted price every year,” Sister Helena says.

Prasad says he also began selling self-help books as they are very popular.

Perfect binding, imperfect reader

Though audiobooks are trending among youngsters, most of them feel that nothing can be compared to the written word.

Bliss, 20, a student of literature at Lady Keane College, says, “I love to read, but good bookstores are rare. Hence, I order books online.”

Monalisa Hazarika, 21, student, says, “Even as school-goers, we would be excited to visit book shops, but after the advent of e-books, that charm disappeared.”

She says, “We do want to read books beyond our syllabus, but I hardly find books I like in the stores these days. One can only find pulp-fiction there. At times, we don’t even find textbooks.”

Hazarika says many of her friends are fond of audiobooks as they allow them to multitask.

She says audiobooks save time, space and energy.

Hazarika, who visits the State Central Library regularly, says, “The quality of books at the library is poor. The authorities rarely stock up on new and interesting books. Most libraries do not have books which we can relate to.”

Teachers’ take

Eudora Khonglah, professor at the Department of English in Lady Keane College, says, “Reading is no doubt on the decline but why blame technology or social media?”

“The gems of thought that fall on a printed page cannot be compared to those that appear on a mobile screen or in a theatre,” she says.

“Books always offer more than any technology can. Our mindset, our ignorance about the rewards of reading stand in the way of cultivating any reading habit and prevents us from living meaningful lives.”

Shailin, a teacher at Eriben Presbyterian Secondary School in Nongrimbah, says, “I feel school students have suffered a lot due to the pandemic. They have started spending more time at home. Their homework went up and they did not get one-to-one attention from their teachers.”

“Students are left with no time to read things beyond the huge syllabus,” she says.

“Education begins at home. Due to lack of time, working parents are unable to pay attention to their children. Students have turned to YouTube and online study material for help. However, such material comes with a lot of factual and spelling errors and there’s no one around to keep a tab on such ‘learning’,” she says.

“Students hardly get to spend 45 minutes once or twice a week in school libraries, which is not enough. Most schools do not even have proper reading rooms,” she says.

“Libraries should be able to cater to various age groups. Sometimes children are forced to read the same set of books for years and they tend to get bored. In such a scenario, they turn to social media platforms such as YouTube and Pinterest as they can get access to a variety of content,” she says.

“Moreover, students get exposed to a lot of creative content on social media. I feel older family members should set an example for younger ones and inculcate the habit of reading in them,” she adds.

All in all, Shillong is perceptibly less book-bound these days which is a worrying factor for the ardent advocates for inculcating book reading habit, not to speak of the book sellers themselves.