By Vishnu Makhijani

What exactly is the extent of the wealth amassed by the Scindias, the erstwhile ruling family of Gwalior? How was it generated and how is it to be distributed among its four claimants?

Other questions are perhaps best hidden away or kept out of sight for diplomatic reasons — such as the Gwalior monarchs’ controversial role during the events of 1857, the alleged and under-probed role of the palace in the assassination of Mahatma Gandhi (enunciated by Tushar Gandhi in a magazine interview in May 2019), and Rajmata Vijaya Raje Scindia’s excessive dependence on her ‘Rasputin’ that led to a bitter split from her son Madhavrao Scindia.

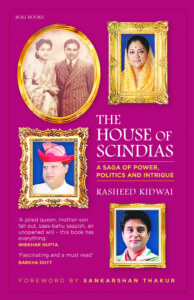

These are some of the questions raised in political analyst, columnist, author and journalist Rasheed Kidwai’s biography, “The House of Scindias “A Saga of Politics, Power and Intrigue” (Roli Books), that provides a wealth of information on the family from the turn of the century and is sure to rekindle interest in a clan that has seen a member serve in parliament or a state assembly for over 60 years.

“The history of the Scindias is best told through their lawsuits over property,” Kidwai writes, and poses the question: “How about a 400-billion-rupee property dispute? Or is the figure higher?”

“The answer is no, if one goes by the affidavits the Scindias have filed for parliamentary and assembly elections from 1957 (when the Rajmata first entered the fray) till date. Their wealth appears to be far less than popular perceptions about what is being fought over in protracted legal battles across the country. According to some estimates — it is impossible to arrive at a definitive figure — these disputes are over properties worth around Rs 40,000 crore. Some of these disputes have been dragging on for over thirty years among the former royals of the erstwhile Gwalior state, Jyotiraditya Scindia and his three aunts, amid speculation that the legal battle may be settled out of court,” Kidwai writes.

“The answer is no, if one goes by the affidavits the Scindias have filed for parliamentary and assembly elections from 1957 (when the Rajmata first entered the fray) till date. Their wealth appears to be far less than popular perceptions about what is being fought over in protracted legal battles across the country. According to some estimates — it is impossible to arrive at a definitive figure — these disputes are over properties worth around Rs 40,000 crore. Some of these disputes have been dragging on for over thirty years among the former royals of the erstwhile Gwalior state, Jyotiraditya Scindia and his three aunts, amid speculation that the legal battle may be settled out of court,” Kidwai writes.

“Neither side has denied or confirmed anything related to their legal battles, let alone reveal any details,” he adds.

The roots of the dispute lie in the fact that when Jyotiraditya’s grandfather, Jiwajirao Scindia, the erstwhile Maharaja of Gwalior, died in 1961, he had not left instructions about how his immovable and movable properties were to be divided among his descendants.

“The properties were initially divided equally between his widow, Vijaya Raje and his only son, Madhavrao, after she filed a suit in the Bombay High Court, back in 1984. Mother and son both had 50 per cent share in the large number of immovable properties spread across India.

“In his case, Jyotiraditya had invoked the Scindia custom of primogeniture,” Kidwai writes. He claimed that the provisions of the Hindu Succession Act that normally divide property equally among the descendants do not apply to the princely line as these were excluded by Section 5 (2) of the Act relating to the inheritance of a family. His aunts, Usha Raje (settled in Nepal), Vasundhara and Yashodhara contested the claim, citing their mother’s will of September 20, 1985.

Sardar Sambhajirao Rao Angre, “a master of intrigue and former private secretary to Vijaya Raje, who had a factious relationship with Madhavrao” stepped in, Kidwai writes, “to explain that the custom of the firstborn enjoying ‘jyeshtbadhikar’ (primogeniture) could not be established beyond doubt as almost everyone who had ascended the throne of Gwalior before Jyotiraditya’s great-grandfather, Madhav Maharaj, did had been adopted. That was how the Scindia’s had managed to avoid the Doctrine of Lapse that eventually led to the 1857 rebellion by the Rani of Jhansi, Lakshmibai”.

Then, immediately after Vijaya Raje’s death in 2001, Angre produced her handwritten will drafted in 1985 that had disinherited her son and grandson while bequeathing two-third of the assets to her daughters and one-third to a charity through a trust that would, in turn, cover the 15 trusts she had formed in 1975, just before the Emergency, to manage the properties.

“While the legal feasibility of an umbrella trust is questionable, this will is being examined in a probate case by Delhi High Court and is currently in the stage of evidence,” Kidwai writes.

Vijaya Raje’s solicitors in Mumbai had produced another will in 2001that excluded not only her son and grandson but the charities as well, leaving the entire block of properties that was under her control to her daughters. This will is also being examined in a probate case, this time by the Bombay High Court, and is in the evidence state.

The two wills “are important because of an agreement in 1971 when Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had scrapped the system of privy purses. At that point, the Scindias were getting Rs 25 lakh annually, apart from incomes from various trusts”, Kidwai writes.

Immediately after that, the Scindias had divided their assets through a verbal agreement: the immovable properties had gone to the mother and the cash, shares and debentures to the son. A Mumbai court formalised this in 1975.

In his suit, Jyotiraditya challenged the verbal agreement of 1971 and the subsequent court division of 1975 between his grandmother and father.

In October 2017, Jyotiraditya expressed a desire for an out-of-court settlement and for this agreed to the appointment of a commissioner, who, however, died during the process.

In June 2019, “the prospects of a compromise suffered a setback when the Bombay High Court refused a request by Jyotiraditya to strike off a fresh written statement by his aunts, claiming that they had retracted from their earlier stance in the family’s property dispute”, Kidwai writes.

“With Jyotiraditya joining the BJP in March 2020, many in Gwalior and Bhopal feel that the growing cordiality among the nephew and his aunts Vasundhara and Yashodhara (Usha Raje doesn’t take any interest in the case) will help resolve the property disputes,” Kidwai adds.

This, then is the lead-up to a tale that Kidwai relates in eight chapters, beginning from “Scindias: A Brief History” and weaving though “The Rajmata of Gwalior”, “Madhavrao Scindia: In Retrospection”, “Vasundhara Raje Scindia: Princess in Public Life”, “Yashodhara Raje Scindia: Princess Crusader of Many Causes”, “Jyotiraditya Scindia: The Ambitious Gwalior Royal”, “Next Generation: Royals and their Political Future”, and “Various Shades of Fortune and the Ugly Property Wars”.

How will this saga end?

“Following an injunction from the Supreme Court, no property can be given to anyone in the Scindia family till the primogeniture case is settled.

“While the extent of the Scindias’ wealth defies speculation, (by itself) the 1,240,771 sq ft Jai Vilas Palace’s opulent interiors may give an idea. It leaves no doubt in our minds of the vast fortune at stake for the members of the erstwhile royal family,” Kidwai concludes.

Come to think of it, here’s a readymade scenario for an OTT magnum opus. (IANS)