By Ranjita Biswas

Look at that ubiquitous pair of Jeans, can you imagine it in any other colour than denim blue? No matter if today you can get them in other hues, and black too, but the fact remains that the image that comes to mind when talking about the popular apparel is its signature indigo blue colour. Period.

But how and why has the indigo colour come to pervade our imagination?

But how and why has the indigo colour come to pervade our imagination?

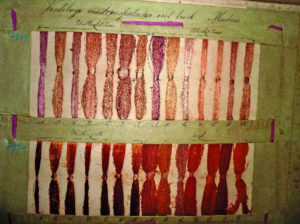

“…The world’s only source of natural blue dye was species of indigo bearing plants. They supplied hues ranging from palest sky blue to the deepest midnight,” writes Jenny Balfour –Paul in the article “Indigo: From Bengal to Blue Jeans” in Reading on Textiles, an anthology of articles on the subject published by leading arts magazine ‘Marg’ on completion of its 75th anniversary of publication.

Many other facts come up in the article. Like, why was indigo such a prized dye in the past, that is, until it could be artificially produced in the lab?

Here comes the India connection. By the time of the Indus civilization, indigo’s chemical secret had been discovered by Indian master dyers and it greatly influenced its global history. Nila (meaning dark in Sanskrit) spread to SouthEast Asia as well as to the Arab world (an-nil in Arabic). In fact, the word indigo is derived from the Greek word indikon (a substance from India).

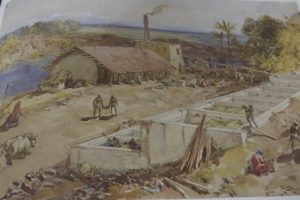

With a chemistry and manufacturing process unique among natural dyes, the writer says, indigo is suited for all types of fibres : ‘royal blue’ for silks for the aristocracy, as also for linens, woollens and cottons for working people and for service uniforms (note the English terms ‘blue-collar worker’ and ‘navy blue’). So a great amount of indigo was needed to supply the ever-hungry textile manufacturers during the colonial times. Vast tracts of land in Bengal, Bihar and eastern UP saw indigo factories cropping up. On the flip side, they were also sites of rampant exploitation of the poor workers. Even some sensitive junior British officers in charge wrote on the plight of the workers.

The general public in Bengal became aware of it after reading the play Nil Darpan by Dinabandhu Mitra (1860). It was translated into English by renowned poet Michael Madhusudan Dutta (1861) as The Mirror of Indigo. As the book reached beyond the seven seas, it created a hue and cry in the British Parliament. Back home too, the labourers at last rose in rebellion. Ultimately the indigo factories were dismantled.

But the love for the indigo remained. After much research, synthetic production was made possible. A new story was woven when German origin emigrant Levi Strauss in America hit upon the idea of turning out workaday overalls to miners and cowboys with imported indigo dyed material. During the Second World War II, the GIs wore ‘jeans’ and were followed by film stars and others. The rest is history, as the clique goes.

The story of indigo is just one of the many highly researched pieces appearing in the Marg anthology, all written by experts in the field, that throw light on the textile heritage of India. For example, how many of us know that a 200 –year-old Indian trade cloth, treasured as sacred on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi may be linked to a weaving tradition of medieval India? (‘Of merchants, monarchs and monks: An 18th century Patolu re-examined’: Shilpa Shah). The famous Patola saree’s heritage goes back to Patan, capital of the12th century Solanki dynasty in Gujarat. The sample found in Indonesia shows an elephant in procession.

The story of indigo is just one of the many highly researched pieces appearing in the Marg anthology, all written by experts in the field, that throw light on the textile heritage of India. For example, how many of us know that a 200 –year-old Indian trade cloth, treasured as sacred on the Indonesian island of Sulawesi may be linked to a weaving tradition of medieval India? (‘Of merchants, monarchs and monks: An 18th century Patolu re-examined’: Shilpa Shah). The famous Patola saree’s heritage goes back to Patan, capital of the12th century Solanki dynasty in Gujarat. The sample found in Indonesia shows an elephant in procession.

An interesting spread in the collection illustrates how in the newly independent country manufacturers used tools like labels attached to clothes or advertisements. Looking at the ads of those early years they may look quaint compared to today’s generation used to high profile shoots, but they reflect an evolution of fashion trends, as we look at ads of Khatau voiles, Mafatlal’s ‘the dress of the people’, D.C.M. tapestries, etc.

Marg’s founding editor Mulk Raj Anand wrote (Warp and Woof, 1982) that,

“Pride is supposed to be one of the deadly sins in the eyes of the pure. And yet in our country, generation after generation, our ancestors took pride in the achievements of the craftsmen, who made fabrics for the Nagarakas and Nayikas to wear, as it gave them dignity and self- respect. And it was the pride in the costumes worn, that brought the skill of millions of weavers, dyers and printers, to the creation of fabric from the earliest times.”

Indeed, textile and weaving with different materials are India’s proud traditions. Doyens like Kamaladevi Chattopadhyay and Pupul Jayakar, who were behind the revival of cottage industry and handicrafts in the post- Independence period have all written illuminating articles on issues in the past. That the magazine continues to publish while the country also celebrates 75 years of independence deserves accolades indeed.

Trans World Features