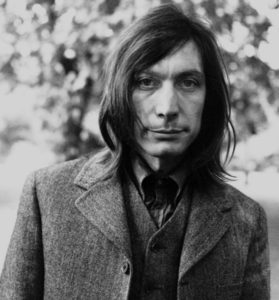

In an era when rock drummers were larger-than-life showmen with big kits and egos to match, Charlie Watts remained the quiet man behind a modest drum set.

But Watts wasn’t your typical rock drummer.

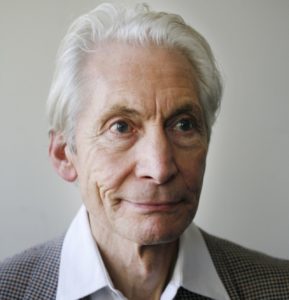

Part of the Rolling Stones setup from 1963 until his death on Aug. 24, 2021, Watts provided the back-beat to their greatest hits by injecting jazz sensibilities – and swing – into the Stones’ sound.

As a musicologist and co-editor of the Cambridge Companion to the Rolling Stones – as well as a fan who has seen the Stones live more than 20 times over the past five decades – I see Watts as being integral to the band’s success.

Like Ringo Starr and other drummers who emerged during the 1960s British pop explosion, Watts was influenced by the swing and big band sound that was hugely popular in the U.K. in the 1940s and 1950s.

Modest with the sticks

Watts wasn’t formally trained as a jazz drummer, but jazz musicians like Jelly Roll Morton, Charlie Parker and Thelonious Monk were early influences.

In a 2012 interview with the New Yorker, he recalled how their records informed his playing style.

“I bought a banjo, and I didn’t like the dots on the neck,” Watts said.

“So I took the neck off, and at the same time I heard a drummer called Chico Hamilton, who played with Gerry Mulligan, and I wanted to play like that, with brushes. I didn’t have a snare drum, so I put the banjo head on a stand.”

Watts’ first group, the Jo Jones All Stars, were a jazz band. And elements of jazz remained throughout his Stones career, providing Watts with a wide stylistic versatility that was critical to the Stones’ forays beyond blues and rock to country, reggae, disco, funk and even punk.

There was a modesty in his playing that came from his jazz learning. There are no big rock drum solos. He made sure the attention was never on him or his drumming – his role was keeping the songs going forward, giving them movement.

He also didn’t use a big kit – no gongs, no scaffolding. He kept a modest one more typically found in jazz quartets and quintets.

Likewise, Watts’ occasional use of brushes over sticks – such as in “Melody” from 1976’s “Black and Blue” – more explicitly shows his debt to jazz drummers.

But he didn’t come in with one style. Watts was trained to adapt, while keeping elements of jazz. You can hear it in the R’n’ B of “(I can’t Get No) Satisfaction,” to the infernal samba-like rhythm of “Sympathy For The Devil” – two songs in which Watts’ contribution is central.

And a song like “Can’t You Hear Me Knocking” from 1971’s “Sticky Fingers” develops from one of Keith Richards’ highest caliber riffs into a long concluding instrumental section, unique in the Stones’ song catalog, of Santana-esque Latin jazz, containing some great syncopated rhythmic shots and tasteful hi-hat playing through which Watts drives the different musical sections.

You hear similar elements in “Gimme Shelter” and other classic Rolling Stones songs – it is perfectly placed drum fills and gestures that make the song and surprise you, always in the background and never dominating.

“On the hi-hat, most guys would play on all four beats, but on the two and the four, which is the backbeat, which is a very important thing in rock and roll, Charlie doesn’t play. It pulls the time back because he has to make a little extra effort.

And so part of the languid feel of Charlie’s drumming comes from this unnecessary motion every two beats. It’s very hard to do – to stop the beat going just for one beat and then come back in … And the way he stretches out the beat and what we do on top of that is a secret of the Stones sound.”

A jazz sensibility in a rock format

While the Stones’ most obvious musical inspiration was the blues, Watts’ drumming had the fluid yet disciplined tendencies of jazz. Few would say he pulled the Stones in an overtly jazzy direction – this would be something he would explore more fully later through side-projects in the 90s, including a big-band and a jazz quintet. But his jazz underpinning would help the band incorporate other genres into their repertoire, from reggae to funk, which helped expand what a rock sound was.

One such sound was the Afro-Cuban mambo groove, which he became familiar with via big band music. This allowed him, as drumkit historian Matt Brennan points out, to play seamlessly alongside conga player Kwasi Dzidzornu on Sympathy for the Devil, which opened the landmark Beggars Banquet album when the Stones sought to broaden their palette in the late 60s.

While he was able to stretch out across genres, Watts’s playing was uncharacteristically unflashy for a drummer in a rock band. Brennan identifies a set of traits that, in the popular consciousness anyway, are associated with rock drummers – being primal, powerful, virtuosic and exhibitionist. On the face of it, Watts displayed none of these.

Unlike Led Zeppelin’s John Bonham, he was not an especially powerful hitter. He lacked the quixotic flair of The Who’s Keith Moon, and his playing was far removed from the complex virtuosity of the prog-rock and fusion players who emerged in the 1970s, or indeed, his jazz influences like Roach.

Self-effacing as well as self-taught, for Watts, serving the song was key.

“I try to help them get what they want”, he said of Jagger and Richards. “I don’t think what I do is particularly difficult. What is good, though, is that people look at me and say, ‘Well, I can do that’”. But doing what he did is not as easy as he made it sound.

Modesty and distinctive simplicity

Watts’s hallmarks were simplicity and a feel that provided both space and a solid base for Keith Richards’ open-tuned swagger on guitar. The Stones groove derived from how Watts played infinitesimally behind the beat, which Richards has attributed to his distinctive style, and credited as foundational to the Stones sound.

The Stones, then, relied almost as much on what he didn’t play – on the space he left – as on what he did. Watts himself said, “there are a million kids who can play like me”. But it was his deceptively difficult and idiosyncratic playing that propelled hits such as Honky Tonk Women and Start Me Up.

In Honky Tonk Women, this can be heard in the slight mismatch between the cowbell and his drums. Then again in the way he subtly pushes the tempo as the song nears its conclusion, which makes it simultaneously a standard rock beat with a tinge of funkiness – without overt syncopation.

“No Charlie, no Stones”, Keith Richards has repeatedly stated. His passing will surely test that claim to its limits. Ultimately, he shaped rock and roll by ignoring its expectations. “Charlie’s good tonight, innee”, said Jagger on the live 1970 album Get Yer Ya Yas Out. This was both true, and beside the point. Modest, understated and reliable in a musical world characterised by volume, extravagance and mercurial personalities, Charlie was always good on the night.

Powering the ‘engine room’

So central was Watts to the Stones that when bassist Bill Wyman retired from the band after the 1989 “Steel Wheels” tour, it was Watts who was tasked with picking his replacement.

He needed a bass player that would fit his style. But his choice of Darryl Jones as Wyman’s replacement was not the only key partnership for Watts. He played off the beat, complementing Richards’ very syncopated, riff-driven guitar style. Watts and Richards set the groove for so many Stones songs, such as “Honky Tonk Women” or “Start Me Up.” If you watched them live, you’d notice Richards looking at Watts at all times – his eyes fixated on the drummer, searching for where the musical accents are, and matching their rhythmic “shots” and off-beats.

Watts did not aspire to be a virtuoso like John Bonham of Led Zeppelin or The Who’s Keith Moon – there was no drumming excess. From that initial jazz training, he kept his distance from outward gestures.

But for nearly six decades, he was the main occupant, as Richards put it, of the Rolling Stones’ legendary “engine room.”

(Courtesy: The Conversation)