By Esha Chaudhuri

Shot after shot, catching people in their quotidian schedule, Sunday Shillong engages with documentary filmmaker and photo teller, Tarun Bhartiya on his many accounts of people’s lived stories. Accentuating political themes in the backdrop, Bhartiya captures visuals in the digital, leaving them to the beholder’s imagination, subject to perception.

In conversation with the picture maker, Bhartiya on World Photography Day which is themed “Pandemic Lockdown through the lens” this year, Sunday Shillong unravells his personal experience amidst COVID-19 protocols, explores facets of photography and its genres, along with his path in this creative field. Excerpts of the interview are as follows:

As they say, Photography is a moment captured in time. What are your thoughts on it?

Photography only at its most banal will be seen as a technological means of ‘capturing a moment’ and making that image infinitely reproducible. This ability to freeze the moment and make it copyable is what

distinguishes it from traditional fine arts like painting and sculpture. If that was all it takes to make photographs, then CCTV cameras would be the ultimate destiny of photography. Making a photograph – a family snapshot or a selfie or those cute sunset over waterfalls or some gritty street scene or journalistic recording of events is about human choices. Which moment to capture? From where do you capture it? How do you capture it? Once recorded in your camera of many images of the ‘same’ scene, which one would you like people to see? For instance, Nohkalikai does not look like the photographs at all.

Once I became conscious of making that choice and the inherent responsibility that is imposed on the imagemaker I started learning photography. But it is not all meaning making and all that. I quite often follow

Gary Winogrand’s throwaway quip, “I photograph to see what the world looks like photographed”

The photos you click often capture people in their everyday life. What stories do you wish to convey through them?

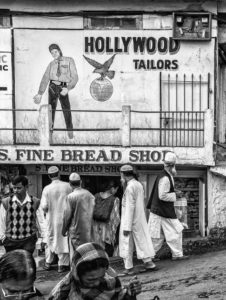

I am a lazy but an incorrigible photographer, as in mostly I don’t go out intentionally to take photos, I take photos while living my own everyday life, meeting people, shopping for essentials, attending union meetings or even walking around Shillong aimlessly. Especially in the last few years, I have been photographing almost on a daily basis, some planned — as a part of my explorations of certain themes… but mostly unplanned. Somewhere I think, images will let me hold on to moments or at least allow me to subject my experiences to some sort of analysis. In that sense, my photos are ‘autobiographical’, they carry within

Laitumkhrah, ShillongFrom NiamBook – book of faith

themselves meanings and interests that my everyday life has for me. Can we imagine our lives without other lives and their struggles and aspirations? Maybe that’s why ‘everyday life’ occupies quite a lot of my headspace and photos.

But on the other hand I also am conscious that my photos are not mirrors in which every day is memorialised as just a record. I want my photos to carry that questioning/critical relationship that I have with my own life as well as the society and community I am part of.

How much of your documentary filmmaking aspect of creativity has a bearing on photography? Would you say they’re interconnected?

I have been running away from ‘moving images’ for some time — trying to photo-graph the ‘instant’ — its arbitrariness, its ability to be personal and portable. I am fascinated with the possibility that the photographs

can become physical objects, arrested in time — a book, a print — a myth which you can hold on to. How else would I like these times to be bequeathed to my grandchildren?

I have started describing myself as Documentarian hoping that will allow both my interests in moving and still images to live in the description. I studied to be a filmmaker and documentary films was what I wanted to do. Does that influence my photography? Yes but not in the image making way of it, because film and photography elicit from you two quite different modes of thinking.

What is common amongst your photographs is that they’re largely (if not all) in black and white. Is there a particular reason for it?

I usually photograph in black and white. Although I am not averse to colour, black and white has become

sort of a habit. Makes me feel old-fashioned. I find it easier to imagine in monochrome. My still camera is usually set in the black and white mode. There are obviously some narratives I think in colour, like my long term work on sitting rooms tentatively titled Hynniewtrep Rooms. I found that colour helped me to understand the meaning of the spaces much more.

Your works also touch upon political issues in subtle fashion. Would you deem this a form of expression as a medium for the larger masses or those holding positions of power?

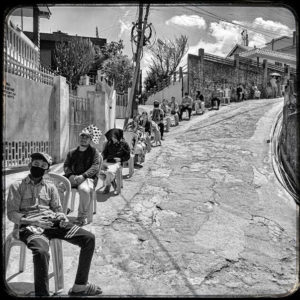

I have never hidden my politics. Politics for me is about the way I see, live and understand the world. Politics is also about questioning the way power operates, what it wants us to see, what it wants us to forget. So, if you see my recent work “Unaddressed Picture Postcards from Khasi Hills”, 100 picture postcards that were exhibited as part of the Chennai Photo Biennial and Diffusion at the Welsh International Festival of Photography, is a sort of an intervention in the kind of reorganisation of Indian state by monolithic ideas of nationalism. This work is a culmination of fifteen years of photographing faith in the Khasi Jaintia Hills.

2006, Mawsynram, Khasi Hills

My own image making all through these years has often not been a ‘time-bound’ project with deadlines and definite sets of questions whose answers I want to illustrate. Somewhere along this journey with the changing public/political discourse in India with its politicisation of the question of faith, religion and National identity, my own ‘private’ curiosity about the ‘why’ and ‘how’ of faith started changing. You can say history and politics made its rude appearance.

As someone who lives in Meghalaya, how come we don’t see its beauty in your photos? When photographing, is the staggering beauty of the landscape a distraction or a blessing?

A place is neither beautiful nor ugly. It can be less polluted or more, or have more rain than some other place or even more cafes than the other. This touristy Indian emphasis on its frontier societies like Meghalaya is a patronising attempt to possess places, societies and communities to sell an Edenic myth. Beauty in its touristy iteration is a form of denial and deception. Imagemaking in Meghalaya is predominantly a decorative art, a waterfall, a sunrise, well costumed cultural artifact.

But there can be another way of looking at beauty, beauty as a way to ‘witness the splendour’ of the world itself, subject the discordant to questions and doubts. Beauty as a process of finding meaning. ‘Staggering beauty of landscape’ at least for me is not a ‘distraction or blessing’ but an experience pregnant with historical, cultural and political realities which require interrogation of image-making (and that may be ugly).

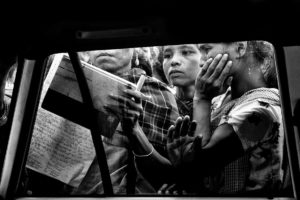

During the lockdown, you had taken a journey travelling through Meghalaya, Assam, West Bengal and Bihar. This was photo-documented amidst lockdown measures, restrictions and the protocols. Tell us about it.

After my father retired from NEHU, Shillong, my parents have lived in Simari, a village in Madhubani district of Bihar. My father had not been doing well in terms of his health, so just before the pandemic got officially acknowledged in February 2020, we had visited them. So when the pandemic picked up, I felt reassured that they were safer in the village where they seemed happier and less tense. Then my father’s health crashed in May. I had to see him and be with my mother. But with no official inter-state transportation and flights still suspended and on top of that the fear of the virus itself, the question was how do I get there. I convinced a tourist taxi driver from Shillong (who was from Bihar) to make this journey with me. Angela (my wife) and I ran around for a transit pass. We then packed lots of food and water and I left early in the morning for the 1200-km journey through four states. I was just thinking of my father. Full of fear and sadness trying to grab on to any hopeful thought I had.

And then I started reaching for my camera, first to distract myself, and then realising that the almost post-apocalyptic landscape I was driving through needed to be remembered and reflected on.

All this has become part of Khlambook, a photo narrative about the pandemic.

Which photographer/artist is among your favourite? Have they had an iota of influence in your journey as a photographer?

I laugh at the idea of ‘original talent’ untouched by influences. There are too many photographers whose work makes me want to take photographs. For instance, Atget or Cindy Sherman – my photography is not in their mode but their photos speak to me. Or Satish Sharma, a photographer whose work that I saw when I was in college remains in my head. But more than these well known photomakers, I try to learn from the local photographic practises I see on social media, for instance, a Shillong photographer who I follow with excitement is Daniel Ranee – I have no idea who this young person is but his photographs of Shillong rooted in Gothic imagery is something that makes me think. Or for that matter Jim Ador Mawlong, whose photographic observations about Khasi Hills will last beyond all touristy photos or Conrad Syiem, making images in the old fashioned nineteenth century way or Ama Collective, a collective of women photographers from Northeast India, I am an inveterate consumer of the weird and obscure.

Everyone is a photographer now – one only needs a phone with a camera. Would you agree?

It is great that now everyone can make images, and can remember their moments. But the photography world with capital P, at least locally, is not too pleased with this democratisation of technology. So, on the one hand we have the mobile world and on the other, a proliferation of expensive cameras, camera flack jackets, bank breaking lenses that photographers love to flaunt. But interesting images are being made by anonymous photographers too.

What, according to you, makes for a good photograph? Which is the best photograph you’ve clicked among the many? Give us (the readers) a window into it.

I have no idea what makes a good photo, there are photos of mine that I like and there are those that I don’t. But even the photos I don’t like, as it happens, start making sense many days or years later. Having said that, I don’t go out to take good photos but photos that mean something beyond the exposure, tone or focus. For instance this photo of Late Kong Spility Lyngdoh Langrin taken in 2006 is a photo that has had various journeys, both personal and public. During my first meeting with Kong Spility, the matriarch of Domiasiat who refused to allow uranium to be mined on her land even when offered 45 Crore rupees for a 30 years lease of her land, she said, “Money will not buy my Freedom”. She was not that well known then outside the anti-uranium groups.

Is it a good photograph? I don’t know but I know it is a meaningful photograph that will have a life beyond being a photograph.

———End of Interview———-

Through his photo documentaries, Bhartiya succinctly bridges gaps between physically distanced people through his vivid journaling, especially during the lockdown phase. Albeit in monotones, the sea of emotions highlights itself in many shades of sepia and colours, an art form that Bhartiya is acknowledged for.

Tarun Bhartiya is a documentary filmmaker and photographer, Hindi poet and political activist based in Shillong.