Mukund Viswanadha was in high school, just finding his way as a young adult, when he received news that changed everything.

“I lost a classmate of mine to suicide,” said Viswanadha, who is now studying biological sciences at the University of Missouri. “His mom, who was a doctor, gave a presentation about how mental health in the Asian American community in St. Louis was lacking, and how there’s a lack of resources devoted to addressing these concerns.”

Viswanadha said “telemental health” — or the use of technology to provide mental health services remotely – could really help increase resources and accessibility to needed care in his community.

This approach has been on the rise in India, where Viswanadha’s family comes from, as well as in the U.S., where he was born. Why? Proponents say it makes talking with therapists more convenient, eliminating things like traveling and waiting rooms, and reduces the stigma that still sometimes surrounds getting care

for mental health. Such benefits are boosting services such as BetterHelp – which is based in the U.S. but can serve patients anywhere.

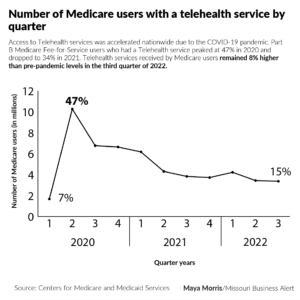

The concept of telemedicine was first introduced in the 1950s as a way to provide medical care to remote and underserved areas. It became more prominent during the COVID-19 pandemic, as practitioners were advised to move their services online.

In recent years, more and more people have turned to telehealth for mental health care. A 2021 national public opinion poll of U.S. adults by the American Psychiatric Association found that 38% of Americans have used telehealth to meet with a medical or mental health professional, up from 31% in the fall of 2020. Nearly six in 10 survey respondents said they would use telehealth for mental health care.

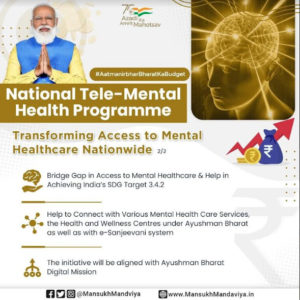

In India, the national government recently launched a telemental health program that will provide free consultations and involve the National Institute of Mental Health and Neuroscience and 23 telemental health “centers of excellence.”

Some Asian immigrants to the U.S. say telemental health could be a boon for them because it provides an easier way to find therapists who understand them. It could be a way students and experts in the Pan-Asian community can achieve their goals of addressing mental health stigma and bolstering culturally-informed care.

But while telemental health can remove barriers to help, some people worry that remote therapy visits limit interpersonal connections. And access to online health services may be hindered in low-income communities, where some people lack reliable internet or expensive new technology.

Still, the trend shows no sign of slowing.

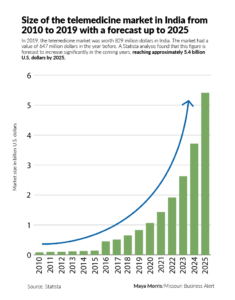

Rise of Telemental Health in India

When it comes to mental health care, India for years has faced a huge “treatment gap,” said Dr. Debanjan Banerjee, a consultant psychiatrist at Apollo Hospital in Kolkata.

Banerjee, who is associated with the Bangalore-based National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences Hospital (NIMHANS), is hopeful about recent legislation that provides more funding for mental health. But he sees a lot of room for improvement.

“In spite of these monumental steps, there still remains an 88% treatment gap in India,” Banerjee said. “Only one in six people diagnosed with mental disorders seek professional help.”

Lack of accessibility, along with the stigma attached to mental health, is largely responsible for this gap. In February, India’s finance minister, Nirmala Sitharaman, announced that the government would be launching its national telemental health program.

It wasn’t until the COVID-19 pandemic hit in early 2020 that telemental health truly began to take off in India. With social distancing measures in place and many mental health clinics and offices closed, telehealth became the primary way for people to get necessary mental health services. At the same time, the need for such services went up.

“The pandemic has accentuated mental health problems in people of all ages,” Sitharaman said in her speech at Parliament. “To improve the access to quality mental health counseling and care services, a national mental telehealth program will be launched.”

But as telemental health services become more widely accessible, experts said some questionable sites and services popped up online.

Dr. Jhelum Podder, a practicing psychoanalyst and assistant professor of psychology at Loreto College in Kolkata, said she’s skeptical about anonymous chat rooms and support groups that claim to provide free therapy.

“It sounds incredibly unethical, irresponsible and dangerous to me. There has to be some accountability, but when this is anonymous, there is no accountability,” Podder said. “You never know how the information you put across will be used.”

“The 2017 Mental Health Act, for example, does not recognize counsellors, psychoanalyst as mental health professionals. Only clinical psychologists with RCI registration are recognised as such. So technically, I’m not a recognised mental health practitioner in my own country because I have an international degree. So, there are glitches like this,” she said.

Culturally-Informed Telehealth

As telemental health expands in the U.S., experts and many potential patients want to ensure it is inclusive and that therapists know how to provide the best treatment to people from various cultures.

Viswanadha, a junior who serves as vice president of the Pan-Asian Mental Health Advocacy Coalition, said he wants to expand mental health services for his community on campus—and telehealth could be one avenue.

He’d love to eventually see telemental health available to students.

Immigrant students said they face some particular challenges that can affect mental health.

Viswanadha’s family moved from India before he was born, and he often helps his immigrant parents navigate life in the U.S. He described how this role can be very stressful, in addition to developing his own identity as a second generation immigrant.

“Sometimes there’s been a bit of a clash between those cultures, and I have to learn how both identities affect me,” Viswanadha said.

A fellow leader in the coalition, its president Ma May Si, said the organization’s racial diversity lends itself to cultivating a nuanced understanding of one another’s mental health struggles.

“I’m originally from Myanmar,” Si said. “My experience as a Southeast Asian versus that of Mukund, who is a South Asian, and other members who are East Asians, are totally different.”

“My parents didn’t really speak English,” Si said. “So growing up, I had to be the one translating for them. So my experiences growing up having to learn the culture here, versus my brothers who were born here, it’s not the same.”

Despite the mental health challenges that may come with cultural differences, Si has noticed a positive shift in how her community thinks about mental wellness after COVID-19. She believes that telehealth has opened up opportunities for Asian-Americans to access culturally informed resources such as therapists with similar backgrounds. Some services allow people to search for therapists who would be a good match, and people can choose professionals with whom they feel  comfortable.

comfortable.

“Having an Asian-American therapist that you can go to rather than someone else who might not be able to relate to your experience, I think that’s super important,” Si said.

Meanwhile Becky Beck, a licensed clinical social worker who works with the Columbia nonprofit DeafLEAD, has some reservations about using technology for mental health.

Beck, whose employer offers services to people with hearing loss, has long strived to make mental health support more accessible. To her, this doesn’t just mean having it available in-person and online; it also means ensuring her clients and anyone else can use the technology.

“It’s always super important to include people with different abilities in the room when you’re discussing technology and what’s available,” Beck said.

Also, remote appointments are not a good option for everyone. She said some people who use therapy services benefit from getting out of their home and into a more neutral space. Telehealth doesn’t allow this.

But despite what some see as drawbacks, experts say telemental health continues to become more popular every year and has the potential to significantly widen access to therapy.

Viswanadha said that would be good for people across the globe. Already, he said, “it did make some people more likely to actually address their mental health concerns, or go to a provider, or just go to a professional and seek help.”

(This report is a cross-country collaboration between the students from the Business Journalism department of the University of Missouri, USA headed by Prof. Randy Smith, and young journalists from India. The project is overseen by Laura Ungar, reporter on the global health and science team at The Associated Press, and journalist Sujoy Dhar, founder of the Indian news agency India Blooms News Service.)