By Vikas Datta

It was a zany tale, spun on a somnolent summer afternoon boat ride in 1862 to entertain three young girls, but went on to become an abiding literary and cultural landmark that influenced James Joyce, Vladimir Nabokov, Salvador Dali, Walt Disney, John Lennon, Pink Floyd, Jefferson Airplane, Aerosmith, Lady Gaga, and Tim Burton, among others.

It was a zany tale, spun on a somnolent summer afternoon boat ride in 1862 to entertain three young girls, but went on to become an abiding literary and cultural landmark that influenced James Joyce, Vladimir Nabokov, Salvador Dali, Walt Disney, John Lennon, Pink Floyd, Jefferson Airplane, Aerosmith, Lady Gaga, and Tim Burton, among others.

Not bad for a story of a bored but determined girl who followed a nervous rabbit, moaning that he was getting late, into a bizarre underground world, and then, climbed through a mirror into a parallel world, set out like a chess board.

And in her peregrinations through these strange illogical worlds, she meets the White Rabbit, the Cheshire Cat, the King and Queen of Hearts, the Gryphon, the Jabberwock, Tweedledee and Tweedledum, Humpty Dumpty, the White Knight, and a host of many more.

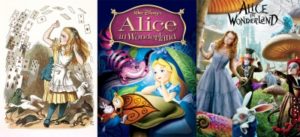

‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’ (1865), or ‘Alice in Wonderland’, as it is more popularly known, and its sequel ‘Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There’ (1871-2) (‘Through the Looking-Glass’ more commonly) stand high both by themselves, and the adaptations that they have inspired across various media.

The appeal of these two books, by Oxford academic and cleric Charles Luttwidge Dodgson (1832-98), who took the pen name Lewis Carroll, can be gauged by the fact that they have never been out of print ever since their first appearance while being translated into nearly hundreds of languages.

The appeal of these two books, by Oxford academic and cleric Charles Luttwidge Dodgson (1832-98), who took the pen name Lewis Carroll, can be gauged by the fact that they have never been out of print ever since their first appearance while being translated into nearly hundreds of languages.

‘Alice in Wonderland’ has at least been translated into 175 languages, including various dialects and even invented languages like Klingon, and has multiple editions in many of them – more than 1,200 versions in Japanese alone, as per one account. Nabokov was the second to translate it into Russian. ‘Through the Looking Glass’ has at least 65.

As mentioned, both the stories were born out of the tale recited on that boating trip in May or July 1862, which so entranced its audience – Alice, 10, and her sisters Lorina, 13, and Edith, 8, the three young daughters of the Dean of a top Oxford college (and later varsity Vice Chancellor) Henry Liddell – especially Alice that she requested he write it down for her.

Dodgson began the very next day. A month later, he told her the plot while on another boating trip, and in November that year, he began writing in earnest.

Dodgson began the very next day. A month later, he told her the plot while on another boating trip, and in November that year, he began writing in earnest.

He was thorough in his written work, researching the natural history of the animals featured and taking the opinion of other children before he presented Alice with a 15,500-word plus hand-written manuscript in November 1864.

Even then, he was busy on a more comprehensive work for publication, expanding the work to 27,500 words by adding the episodes featuring the Cheshire Cat and the Mad Tea Party. It was published in November 1865, with illustrations by John Teniel, the long-time cartoonist with Punch magazine (and the first illustrator to be knighted for his work).

The stories’ plots are too well-known to repeat here but they cannot be dismissed merely as an escapist fantasy.

Alice’s adventures also mark a paradigmatic shift in children’s literature. Not only was it the first example of a children’s book which seeks to entertain rather than teach morals, but the way she enters fantasy worlds has inspired almost every subsequent heroine of the genre – Dorothy into the Land of Oz, Wendy (Peter Pan) into Neverland, and the Pevensie siblings in the C.S. Lewis’ Narnia series.

Like any classic literary work, they can connote different things to different people. Literary experts have detected plentiful allusions to Victorian political and academic matters, most of which are long forgotten, and bountiful examples of wordplay and puns; mathematicians have teased out various mathematical and logical references and concepts in the narrative; one post-structuralist used Humpty Dumpty’s dialogues to explain the concept; and chess experts have discovered a new problem as outlined in ‘Through the Looking Glass’.

And then, the distorted worlds of a dream, with their own unnerving ‘logic’, and on the other hand, the concluding lines of “Alice…” offering a cogent illustration of how the world can impact our dreams came at a time when Sigmund Freud was not even 10 years old!

Then, the impact of Alice’s adventures was not restricted only to inspiring retellings in the genre of fantasy, where apart from the eponymous heroine, several characters have been used in other stories – the Cheshire Cat in Jasper Fforde’s Thursday Next series for one. The character, structure, and form have also freely adapted to teach about subjects ranging from grammar, orchestras, quantum mechanics as well as mocking contemporary politics and economics – of the times of the parodist concerned.

While in Carroll’s own lifetime, Anna M. Richards came out with ‘A New Alice in the Old Wonderland’ (1895), in which a different Alice travels to Wonderland and meets many of the original characters as well as others, the first parody was ‘Gladys in Grammarland’ (1897) in which some fantastical characters crop up to help a rather unstudious girl with her homework.

Then, H.H. ‘Saki’ Munro’s ‘The Westminster Alice’ (1902) has Alice meet various British politicians of the time, right from the ‘Ineptitude’ who currently occupies 10 Downing Street and many other more curious characters, as she understands that lack of logic or sense was not restricted to Wonderland alone. There have been scores since then.

Alice’s adventures have been extensively retold, parodied, or have influenced other works, across media – films (Disney’s cartoon and Burton’s live action one being the most famous), TV and radio shows, opera, plays, paintings, music, comics and manga, video games, and even advertising.

The work has inspired a dozen paintings by Dali, as well as Joyce’s ‘Finnegans Wake’ (‘Alicious, twinstreams twinestraines, through alluring glass or alas in jumboland’).

And then there is Lennon’s ‘I am a Walrus’ and ‘Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds’ which he identified as being inspired by the imagery of Alice, Aerosmith’s ‘Sunshine’ or Tom Petty’s ‘Don’t Come Around Here No More’ as well as Jefferson Airplane’s psychedelic ‘White Rabbit’, Pink Floyd’s ‘Country Song’ and Lady Gaga’s ‘Alice’ (‘Chromatica’, 2020), among many others.

Who says children’s books are only meant for kids? (IANs)