Today, for various reasons, people are exploring their own cuisines that have evolved through generations. Ranjita Biswas talks about a recently published book Porompora by Anuradha Borooah that looks at the uniqueness of Assamese cuisine

By Ranjita Biswas

“Porompora” – tradition, a familiar term for us. Its age-old connotation can be applied to art, music, customs, and food too. India has a mind blowing range of cuisines from different regions, each with its unique condiments, ways of preparing, and even, the ideal mix and match and time of eating advice attached. In our age of buffet platters and introduction of various, even contradictory, dishes on the same table, the regional porompora often takes a backseat.

“Porompora” – tradition, a familiar term for us. Its age-old connotation can be applied to art, music, customs, and food too. India has a mind blowing range of cuisines from different regions, each with its unique condiments, ways of preparing, and even, the ideal mix and match and time of eating advice attached. In our age of buffet platters and introduction of various, even contradictory, dishes on the same table, the regional porompora often takes a backseat.

Yet today, especially after the breakneck speed of modern lifestyle that had to slow down during the pandemic, many people have started taking a look at their traditional food , the knowledge of which has been passed through generations by our grandmothers and great- grandmothers, valuing the goodness and wisdom of old kitchen recipes for a healthy lifestyle.

Anuradha Borooah’s Porompora: Culinary Delights & Customs from the Wondrous Land of Assam focuses on Assamese cuisine. Being in proximity of South East Asia and with free interchange among the people of these regions for centuries, Assamese recipes tend to reflect their influences too. Like the use of sticky rice, bamboo shoot, etc. as also in the cooking style of using less oil, steaming/ boiling rather than over- frying, etc.

The chapters are divided into Rice, Khaar, Lentils, Leafy Greens, Biter dish, Bamboo shoot (bahor gaaz), Chutney, Yam (kosoo) and dry vegetable (bhaji/torkari).

In the Rice section are included Poita Bhaat (panta bhaat in Bengali), a staple of the farmers but now even featuring in restaurant menus in cities for its cooling effect in summer, Kumal Saul (chowl), a soft variety of local rice that does not need cooking just soaking for an hour, Pithaguri- a rice powder, rice with fish intestine, etc.

In the Rice section are included Poita Bhaat (panta bhaat in Bengali), a staple of the farmers but now even featuring in restaurant menus in cities for its cooling effect in summer, Kumal Saul (chowl), a soft variety of local rice that does not need cooking just soaking for an hour, Pithaguri- a rice powder, rice with fish intestine, etc.

Khaar is integral to an Assamese thali usually taken at lunch and as a first course. However, once or twice a week is fair enough and not as an everyday dish. It helps digestion. Khaar is basically alkali or natural soda bicarbonate. Traditionally, the substance is taken out by burning the stem of a mature banana tree and added to the curry, which does not use turmeric , by the way. Different vegetables can be combined to make khaar but raw papaya is very common as the main vegetable. It can be both a vegetarian or non- vegetarian dish. If the latter, adding fried, and broken into pieces head of big fish like Rohu is preferred.

Bamboo shoot is used in different ways in Assamese cooking- and pickled too. The pungent smell is typical to the pickle. But as they say about Durian in S E Asia, it’s an acquired taste, you either love it or hate it. Fresh bamboo shoots fit well with both vegetarian and non-veg dishes.

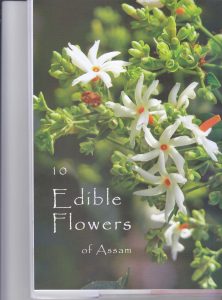

The chapter on Edible Flowers is interesting, throwing light on how housewives have been using locally available greens and flowers ingeniously to turn out stand-alone dishes. Night Jasmine flower (sewali/ seuli in Bengali), pumpkin flower, drumstick flower, even tea flower- abundant in the land of tea gardens , are used in traditional dishes.

Borooah rightly observes in the Introduction that, “…if these [recipes] are not documented by our generation, then they will all become obsolete and lose their value in modern times.”

Profusely illustrated with local names added to the fruits and vegetables and well-designed, the book is a treasure trove of information, especially for the new generation at home and abroad who are interested in culinary art.

The author has wisely added a chapter as introduction to the social customs and festivals of Assamese people which would help the uninitiated to get a glimpse of the land in the Brahmaputra Valley. Cuisine, after all, is an integral part of the socio-cultural milieu of a people.

(Available on Amazon)

Trans World Features