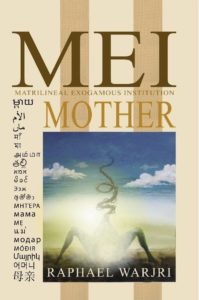

“MEI: Matrilineal Exogamous Institution” released in 2024 and authored by Raphael Warjri (RW) traces the genesis and evolution of the Khasi matrilineal society dating back to times before the advent of organised religion. Founder of Riti Academy and Visual Arts since 1991, Warjri attempts to pay homage to a nature worshipping community, whose centre of the universe is fostered by the powers of ‘meihukum’ or the mother decree.

Giving the mother figure pivotal importance, and recognising the tangible roles of other actors within the system, the author explains why the book is a point of immense discussion. Built on the foundational bricks of of ethics— ‘Kamai ia ka Hok’ earning righteousness,

‘Tipkur Tipkha’ honoring maternal and paternal kinship, and

‘Tipkur Tipkha’ honoring maternal and paternal kinship, and

‘Tipbriew Tipblei’ acknowledging human and divine conscience—became the cornerstones of the Khasi belief system, guiding individuals in their

actions and interactions with others.

Engaging in a dialogue with the eminent artist, filmmaker, playwright and author, Sunday Shillong essays an imagery of the foundations of Khasi society through the lens of Warjri. Excerpts:

SS: Congratulations on your book, how did the idea of writing MEI come about?

RW: When someone asked me about my journey into understanding Khasi matrilineal culture, I was really hoping to learn from a few elders in my society, someone whose knowledge I deeply cherished.

I began delving into the intricacies of the culture, and though I’ve written down what I’ve learned so far, I know that what I’ve penned is just the tip of the iceberg. There’s so much more to explore and understand. Khasi matrilineal practices are incredibly rich and complex, and I feel there’s still much to uncover in order to fully grasp the depth of this culture.

SS: What/who is your inspiration behind writing it?

RW: The inherent understanding of Khasi matrilineal practices has always been a source of inspiration for me, especially through the teachings and experiences of my grandmother, my parents, and other elderly people in our community. Their wisdom has shaped my understanding of our cultural heritage.

However, as I continue my exploration, I’m also eager to connect with several other elders in the community who are deeply knowledgeable but I also believe there’s much to learn from their lived experiences and firsthand knowledge.

However, as I continue my exploration, I’m also eager to connect with several other elders in the community who are deeply knowledgeable but I also believe there’s much to learn from their lived experiences and firsthand knowledge.

SS: How long did it take you to complete the research and writing?

RW: I’ve been collecting bits and pieces for a long time, which I began to put into form by writing articles in vernacular newspapers about a decade ago and subsequently in English newspapers as well as from the stories of my grandmother, my parents, my uncles and I lived with it as we encountered everyday on any social and cultural occasions.

SS: What are some of the archives or historical texts that you referred to?

RW: I’m yet to acknowledge that I am a writer, I’m not an avid reader either, so I have my own way of going through the process of referring to archives. I must acknowledge the initial books Ki Khun Ki Ksiew U Hynñiewtrep by Mr. Spiton Kharakor, and Ka Jymbriew bad Ka Thymmei Longkur Longjait U Khasi by Rev Iarington Kharkongor, different books by my friend (late) Donbok T Laloo the publications of Seng Khasi, as well as online resources to broaden my knowledge on other aspects of matrilineal cultures.

SS: Personally, I enjoyed reading the sections on the nurturing aspects of femininity and womanhood and its celebration within the matrilineal setup of the Khasis. However, in the present times, what are some of the shifts that you see firsthand?

RW: In Khasi society, we celebrate by upholding the sanctity of motherhood bestowed upon the maternal mother as the bearer of the clan and paternal aunt as the provider of a father. At present, those who lack the proper understanding of the essence of Khasi matrilineal customs and easily influenced by the austere patriarchal norm are hellbent to accept and glorify the conventional universal practices, particularly in the so-called ‘enlightened’ sections of society in the urban educated individuals. However, in the rural areas it is embedded in the psyche of the people that no other social influence could bring about any changes.

RW: In Khasi society, we celebrate by upholding the sanctity of motherhood bestowed upon the maternal mother as the bearer of the clan and paternal aunt as the provider of a father. At present, those who lack the proper understanding of the essence of Khasi matrilineal customs and easily influenced by the austere patriarchal norm are hellbent to accept and glorify the conventional universal practices, particularly in the so-called ‘enlightened’ sections of society in the urban educated individuals. However, in the rural areas it is embedded in the psyche of the people that no other social influence could bring about any changes.

SS: Through the reference of the gods, goddesses in your book you invoke reminders of staying away from greed and hatred and sticking to qualities of self-righteousness, harmony, peace and justice. How much of it do you still see as a reality today?

RW: The fact that certain principles no longer seem to be a prominent feature of society today does not mean they should be discarded, especially when we know deep down that they represent the righteous path. All of these qualities are often preached in ways that serve the self-interests of manipulative individuals within society. However, despite these distortions, the ultimate truth remains unwavering.

SS: The book on many counts makes references to Mother Earth and nature. But isn’t what we’re witnessing today all around Meghalaya just quite the opposite of it? The environmental degradation, felling of trees to build fancy houses and buildings and more so the acquisition of land. How do you perceive these happenings?

RW: Mother Earth is often seen as the land that sustains us all— provides us with the resources we need to survive. However, over time, the world has shifted. We’ve started to view everything, including the land itself, as commodities—temporary possessions meant for human use and purposes. This mindset needs to change. The way we interact with nature has become unsustainable, and it’s clear that we need a new way of thinking.

RW: Mother Earth is often seen as the land that sustains us all— provides us with the resources we need to survive. However, over time, the world has shifted. We’ve started to view everything, including the land itself, as commodities—temporary possessions meant for human use and purposes. This mindset needs to change. The way we interact with nature has become unsustainable, and it’s clear that we need a new way of thinking.

One of the key solutions lies in returning to some of the virtues of ancient knowledge systems. These systems were often rooted in a deep understanding of balance and respect for nature.

SS: The book is also a call to the youth to revisit their roots and be proud of their heritage. I agree with you. How do you think the book could positively impact the youth of Meghalaya?

RW: Despite the sweeping changes that have shaped our society, if the younger generation approaches this ancient knowledge without prejudice, they will find that these teachings are not only applicable but also vital for the growth and development of our community in the present era. While a few have managed to stay grounded in the profound wisdom passed down by their forebears, it is them, who hold the potential to steer the future towards a path of genuine acceptance and harmony.

SS: A very pertinent question is, despite the glorification of women and womanhood, why do you think that women in the state do not hold as many positions of power as the men or even their representation remains skewed?

RW: The traditional system in place can be seen as a form of glorification that fosters a balanced distribution of roles between men and women in society and makes a clear distinction between responsibility and power.

RW: The traditional system in place can be seen as a form of glorification that fosters a balanced distribution of roles between men and women in society and makes a clear distinction between responsibility and power.

Traditionally, the societal convention designated women to manage the household or domestic affairs, while men were entrusted with roles outside the home. However, women who exhibited extraordinary intellect, sensibility, and maturity were entrusted with significant functions and supervisory roles within the larger societal framework. Throughout history, there have been instances where women held the position of chiefs, though these examples became increasingly diluted with colonial interpretations that reshaped and often obscured the original societal structures.

The history of our people offers powerful testimonies to the strength and resilience of women, especially in the face of adversity. One such example is Ka Phan Nonglait, who, during the freedom struggle against the British colonial regime, fought alongside male warriors in ambushes that resulted in the defeat of dozens of sepoys, including British officers. In more recent history, women have continued to rise to prominence in various fields, breaking barriers and making significant contributions to society.

SS: What is your opinion on the desire of many people within the Khasi community to abandon the matrilineal custom and adopt a patriarchal system of lineage?

RW: The desire among some members of the Khasi community to abandon the matrilineal system in favor of a patriarchal lineage is a complex and multifaceted issue. It reflects the influence of external factors, particularly colonialism and globalisation, to align with mainstream, global practices.

While it is true that matrilineal systems may face challenges in the modern world, it is essential for the Khasi people to engage in a thoughtful and informed dialogue about the future of their customs. This dialogue should not be driven by external pressures or trends but should focus on preserving the core values of the culture—values that promote inclusivity, respect, and the recognition of both the maternal and paternal influences in society.

While it is true that matrilineal systems may face challenges in the modern world, it is essential for the Khasi people to engage in a thoughtful and informed dialogue about the future of their customs. This dialogue should not be driven by external pressures or trends but should focus on preserving the core values of the culture—values that promote inclusivity, respect, and the recognition of both the maternal and paternal influences in society.

- End of Interview-

Through the book, Warjri acknowledges the sanctity and purity of the bond shared between mother and child, drawing parallels with women’s birth giving capacity and equating that with Mother Earth’s essence of creation itself. Thus, echoing uncanny similarities with the eco-feminist school of thought throwing examples of “Meiramew” revered as the mother of all living beings, and the stone “Ryngkew Basa”, as a hardened form of the earth, is seen as a symbol of fertility and the provider of the seed for the reproduction of life forms are few mentions among many, resounding the same idea. Also, that both converge towards an innate need for its protection and preservation rather than drastic transformation due to external factors.

Together, with the Synjuk Ki Rangbah Kur: Ka Bri U Hynñiewtrep, a collective of Khasi clan elders from across the state, Warjri’s endeavour to raise awareness about the importance of maintaining the matrilineal customs within the society for its sustenance rising above the dominance of brute power has been duly acknowledged and will hopefully be advocated further.

– Esha Chaudhuri