By Sanjana Mohan and Lekha Rattanani

How does a woman in labour walk five kilometers across a hill to reach a clinic at night? What nutrition advice do you give to the family of a severely malnourished young man with silicosis and tuberculosis, who cannot afford to buy milk or eggs? What happens to a sick child when the nearest health facility is 20 km away and there is no transport? How do you counter malaria, diarrheal diseases, cholera, exacerbated by poor sanitation, flooding and malnutrition in remote and rural areas? These are often seen as situations in rural India, but they are not limited to this country. These stories are from across the globe. Despite the huge differences between developing and developed countries, access is a major issue in rural health around the world. Resources are usually concentrated in the cities. All countries have difficulties with transport and communication, and they all face the challenge of shortages of doctors and other health professionals in rural and remote areas. Doctors from India, Australia, America, New Zealand, Norway, Nepal and Sri Lanka discussed these problems at the three-day World Rural Health Summit in Bengaluru that ended on April 06.

Typical medical conferences are restricted to doctors and do not include nurses and public health professionals unless it relates to their areas. Such conferences definitely do not include midwives. This rural health summit opened with a panel of midwives and nurses. The midwife, a healthcare professional trained to support women throughout pregnancy, childbirth, and the postpartum period, plays a key role in low and middle-income countries (LMICs) where access to skilled healthcare providers is often limited. World Health Organization (WHO) figures for 2024 show that there are an estimated 29 million nurses worldwide and 2.2 million midwives. WHO estimates a shortage of 4.5 million nurses and 0.31 million midwives by the year 2030. This poses a major problem as nurses and midwives play a pivotal role in rural healthcare.

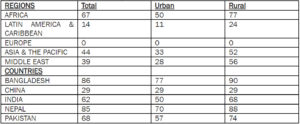

Worldwide lack of access to healthcare services and coverage is as high as 56% in rural areas as compared to 22% of the population in urban areas. Two thirds of the deficit of 10.3 million healthcare workers in the world is in rural and remote areas, says a report by the International Labour Organization (ILO). The report, “Global evidence on inequities in rural health protection: New data on rural deficits in health coverage for 174 countries,” dated May 2015, reveals major health access disparities between rural and urban areas. The disparity is particularly pronounced in Africa, where a large percentage of the rural population lacks access to healthcare (See table).

This table gives the % of population not covered due to health professional staff deficit:

The deficit though felt everywhere, is much higher in low-income countries and those with disparate distributions of wealth. For instance, Nigeria’s GDP is the largest in Africa, but its per capita income of about USD 2,000 is low. It is Africa’s most populous country with 206 million people and has a highly inequitable distribution of income making it both wealthy and very poor. About 40% of the country lives in poverty and in social conditions that create ill health which is addressed with devastatingly high health expenditure from out-of-pocket spending. Nigerian healthcare spending, roughly 80%, is out-of-pocket expenses. This means individuals directly pay for healthcare services, rather than relying on health insurance or government funding. In India, the ministry of health and family welfare says that a steady decline in out-of-pocket expenditure as a percentage of total health expenditure has been observed in the last five years from 48.8% in 2017-18 to 39.4% in 2021-22.

Developed countries also face problems with health care coverage in rural areas. For example, the Netherlands is a small and a developed country with a higher population density and should not have a problem because of milder access issues in rural areas compared to other countries on account of the relatively shorter distances. But the differences in population densities in urban and rural municipalities is large and with increasing migration by youngsters from rural to urban areas, the problems of the rural greying population are mounting. This is mainly because of the demands of the growing healthcare needs of those left behind, which are not being met.

Since 1992, WONCA, the World Organization of Family Doctors, has developed a specific focus on rural health. This is mainly through the WONCA Working Party on Rural Practice, which has drawn attention to rural health issues through World Rural Health Conferences and WONCA Rural Policies. The World Health Organization (WHO) has a Memorandum of Agreement with WONCA which includes the Rural Health Initiative. It was more than 20 years ago that WHO and WONCA held a major WHO-WONCA Invitational Conference on Rural Health. This conference initiated a specific action plan: The Global Initiative on Rural Health. Yet, nothing has really moved. However, the “Health for All” vision for rural people is more likely to be achieved through joint concerted efforts of international and national bodies working together with doctors, nurses and other health workers in rural areas around the world. Australia and India have their own solutions. In Australia doctors working in rural areas are called “rural generalists”, a protected discipline like a cardiologist. They receive incentives to work in rural areas and have in turn contributed to development and changes in the local economy. In India, where rural healthcare issues are starker than those of other countries, there are initiatives underway like sensitising young doctors to the problems in villages and remote areas. In October this year, a group of young doctors from across India will meet at Iswal, a village 25 kms from Udaipur city, to participate in a Rural Sensitisation Programme (RSP) organised by Basic Healthcare Services, a Rajasthan-based non-profit that runs primary healthcare centres in the State. RSP is a three-day field programme that hopes to expose this group to well-functioning primary health facilities on the one hand, and day-to-day lives and struggles of rural, tribal communities on the other. RSP emerged in response to the growing disillusionment among many young doctors who graduate into a real world of corporate hospitals, pharma companies and commissions. Which way should they go? Rural India can provide the answers as it struggles to come out of its health care problems. We will need health services models based close to the community that practice ethical and high-quality healthcare. Rural sensitising may be the way forward for the rest of the world.

(Dr.Sanjana Mohan is the co-founder of Basic Healthcare Services, a Rajasthan-based non-profit that runs primary healthcare centres. Lekha Rattanani is the Managing Editor of The Billion Press) (Views are personal) (Syndicate: The Billion Press) (e-mail: [email protected])