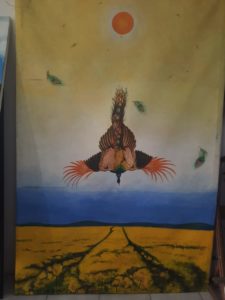

For Raphael Warjri, the spoken word has a way of colouring canvases. Born a Khasi, a community that does not have a visual art form, Warjri has given them wings, such as those of a peacock that has descended from the heavens, only to find that the mustard fields it came to aren’t in reality what they seemed to be.

The colours on his canvases are deep, like the colours the Khasis wear, way richer than the pastels that many find more enduring.

“The history of our community depends on word of mouth. I pick folk tales which convey strong messages to society. They are metaphorical, timeless and relevant to the world,” says the 60-year old artist.

The peacock in its flight to the earth has shed its feathers that now hold up an image of the unachievable against a deep blue sky. The strokes of that one quest has turned a rainbow-coloured bird into a being deep brown, face downward, caught mid-flight in life’s eternal search for change. “The sun and the handsome peacock were wife and husband. Abandoning her was his quest, losing his feathers and not being able to return is the reality he now must face.” The truth is universal, Warjri’s colours just as stark.

Nestled in a modest studio near a rustling stream at Jaiaw Lansning, Warjri’s studio is a mix of acrylic paints and Khasi tales. Folk instruments crafted of bamboo sit pretty in a corner, pieces of a conversation his daughter has with the Khasi soul. “My daughter Dalariti and is into Khasi music,” says the long-haired artist dad.

The endeavour to spread the good word of the hills through the pallette and brush has found a following. Warjri’s Riti Academy of art is now 30 years old and boasts of 30 ardent students.

“The way of the Khasis is different,” he says. “We are a community that cannot boast of too many colour motifs. But when it comes to practicality, we, for example, have a plough that can not only cut tracts on the earth but also weed out plants that will get in the way of our crops.”

Warjri’s creations are expressions of an old and aged soul tempered by the history of a people that is ancient and inhabit the settled, undulating hills of Meghalaya. The anthesis is the encroached of land, life and thought by unearthly ‘civilisation’.

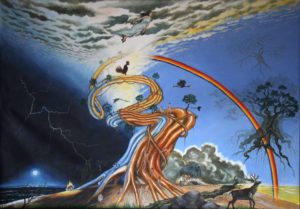

His painting ‘Milestone’ features an unclad man with monoliths, bamboo basket burden of the years on his back. The mountains in the background are still white, while closer, the skyline has now been eaten into by molti-storeyed habitation. A tiger-headed snake, the Nature God of the Khasis, sticks out of the sky, fangs bared, as it admonishes humankind for its follies. Warjri’s “Cosmogeny” is a display of banyan-like roots that grow into the sky and into a rainbow, with a rooster and fairy. “The painting is built on several mythological stories about creation and the legend of the Lapalang stag, a narrative of the lamentations of the mother of a stag that was hunted down by our people for its trespasses into Khasi land.”

In a small house by a rustling stream at Jaiaw Lansning, the folk tales of the Khasis are being retold, this time in acrylic. “Acrylic because it connects more with the audience. I like to keep it simple hence no mixed media,” says Warjri. Simple and spectacular. Just like the iconoclast Khasi.