By Trans World Features

Devashish Makhija is a filmmaker difficult to put into a particular category . But his films compel you to keep glued to the screen. His Bhonsle fetched the National Award for Best Actor for Manoj Bajpeyee recently. Makhija’s new short film Cycle, which is about a wronged young tribal woman turning rebel in the absence of systemic justice, has been  selected for screening at the International Film Festival, Kerala. Shoma A. Chatterji reports

selected for screening at the International Film Festival, Kerala. Shoma A. Chatterji reports

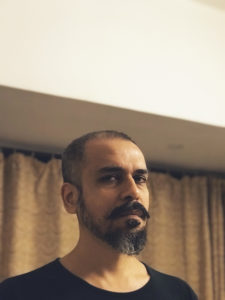

Devashish Makhija has written and directed multiple award-winning short films. He also writes short stories and paints as a hobby.

The new film Cycle is adapted from one of his short stories Forgetting. It has been shot on a phone camera as ‘found footage’, a film technique popularised by the ‘Blair Witch Project’ primarily, among many others. Here the events on screen are typically seen through the camera of one or more of the characters involved, often accompanied by their real-time, off-camera commentary.

In the first part, a smartphone screen shows a tattooed face of an Adivasi girl trying to fight her rapists. She screams for help in an Adivasi dialect but cannot escape rape.

In the second half of the film, you find the same girl dressed up in jungle suits chopping off her hair angrily. She is armed with a rifle, ready to attack. Now the screen turns wider.

However, Cycle is not about bad guys and their victims. That binary of good and evil is merely the symptom. Not the root cause of the problem. “It’s not about the wronged tribal or the abused woman or the oppression of the marginalised – all of which this film appears to be. These are mere access points to hopefully help us turn our lens onto a species that continues to fail its own,” says Makhija.

The film shows a documentary filmmaker team shooting a film on extremists who are not identified by their party or group. The film crew are also threatened at times by the extremists. Are they extremists? Or, are they bent on revenge through violence not only  through rape but against their rights as citizens in general?

through rape but against their rights as citizens in general?

Asked what made him feature documentary filmmakers shooting the so-called Maoists and whether it is being cynical about the crew, he says, “I am not poking fun at anyone. I only have empathy and regard for all such efforts at carrying the voice of those in need of justice to those who refuse to hear those pleas.”

“What we seek to do along the way is to suddenly thrust upon a bloodthirsty audience – the idea of anti-vengeance. And to deny the viewer any brutal satisfaction they expect and seek from a narrative of this kind.”

Makhija’s idea of a blood-thirsty audience is the belief that “All of us have a predisposition to watching violence as a sport… so if someone is being lynched, we will stand by and take perverse enjoyment, which is why revenge is such a successful genre of storytelling.”

But he also wants to deprive viewers of the perverse pleasure of watching someone being butchered for vengeance. “I chose to set the story up for that, and then thwart the act just before it promised to happen,” he says.

Explaining the title of the film, Makhija says, “The film seeks to explore the idea of the ‘Cycle of Violence’ that we are all complicit in.” The film is shot over just three long shots because he wanted to trace the history of violence of one such character in three sharply defined chapters.

“I want to raise questions all the time. We don’t question ourselves enough. We do cruel, illegitimate things to others and to our world, and hope that no one is going to question us. Through my films I hope to make us stop dead in our tracks – even if for just a moment – and think about how horrifically self-centred we have all become,” says Makhija.

He feels that if as a storyteller he doesn’t fulfill some social responsibility, he doesn’t earn the right to practise his craft. “This is entirely a personal viewpoint. But I hold myself to it as ruthlessly as I possibly can. I believe if we have rights as citizens we also have duties. And  raising questions is me doing what I perceive to be my duty as an artist.”

raising questions is me doing what I perceive to be my duty as an artist.”

Cycle is filmed in three uninterrupted long takes. It features a large and ethnically varied cast, most of them facing the camera for the first time.

The film has almost no editing done to talk about. Each scene is one long continuous take, shot after much rehearsal, choreography and work-shopping. The director says that he allows the innate rhythm of the character wielding the phone camera to dictate the speed and movement of the camera. Here the actor becomes the cinematographer.

He points out that it takes years and a lot of sacrifice to make a documentary film. “If the soul doesn’t have enough steel and if the heart doesn’t have enough fire to sustain the filmmaker through those years of self-imposed hardship it’s not possible to make any docu film. No one is only after awards. We all make what we do because if we did not, we would not be able to look ourselves in the eye.”

He hopes that Cycle will question our frightening mob mentality in matters of retribution, and start a conversation around the gaping chasm between collective and individual moralities, to see individuals who are compelled to pick up a gun as a complex product of circumstances, inequalities, fragilities and desperations.

Makhija has an impressive oeuvre. He has written and directed the multiple award-winning short films like Taandav, Elayichi, Agli Baar (And then they came for me), Rahim Murge pe mat ro), Absent, and Happy besides the full length feature films Ajji and Bhonsle.

Ajji is a piercing look at revenge on the rape of a teenager by the girl’s grandmother. Bhonsle fetched the National Award for Best Actor for Manoj Bajpeyee.