Jnanendra Das examines the mystifying case of Sohra’s high rain records and its subsequent water shortage inching closer to losing grips of the tag of ‘World’s Wettest Place’.

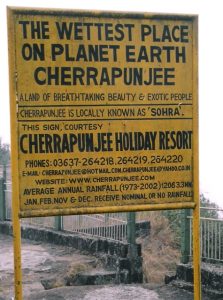

Natives of the state need no introduction to Sohra, and for others, if you have read the NCERT Geography textbooks in school, you must have read about Sohra (historically and to non-Meghalayans still sometimes known as Cherrapunji) as the “wettest place on earth”. Many Geography textbooks mention that it receives the highest rainfall on earth during the monsoons. Over the years, Mawsynram, situated just 15 KM to the west, replaced Sohra and now receives higher rainfall. During the winter months, however, Sohra faces an acute water shortage. This doesn’t add up for the wettest place to face a water crisis, but in reality, erratic rainfall patterns especially in the dry season (November, December, January and February) are to be blamed, along with the increasing population and irreversible environmental degradation globally. Sunday Shillong then explores how the world’s wettest place faces water shortage?

Natives of the state need no introduction to Sohra, and for others, if you have read the NCERT Geography textbooks in school, you must have read about Sohra (historically and to non-Meghalayans still sometimes known as Cherrapunji) as the “wettest place on earth”. Many Geography textbooks mention that it receives the highest rainfall on earth during the monsoons. Over the years, Mawsynram, situated just 15 KM to the west, replaced Sohra and now receives higher rainfall. During the winter months, however, Sohra faces an acute water shortage. This doesn’t add up for the wettest place to face a water crisis, but in reality, erratic rainfall patterns especially in the dry season (November, December, January and February) are to be blamed, along with the increasing population and irreversible environmental degradation globally. Sunday Shillong then explores how the world’s wettest place faces water shortage?

History behind its name

Sohra as it has always been called was pronounced “Cherra” by the British. Located 40 kilometres, North Of Shillong in East Khasi Hills, Sohra eventually evolved into a temporary name, Cherrapunji, which according to many means ‘land of oranges’. But locals say “punji” meaning “a cluster”, was added to “Cherra” by the British-employed Bengali bureaucrats. Another belief is that Cherrapunji’s original name is ‘Sohrapoonjee’. ‘Poonjee’ refers to the head village where the ‘seat of power’ of the Chieftain is. The English who ruled over this place from 1830-1947 could not pronounce ‘Sohrapoonjee’ correctly and named it ‘Cherrapunjee’. Some old colonial period writings refer to it as ‘Chirra’ too. (Sohra Civil Sub-Division). Later the Meghalaya state government renamed Cherrapunji to its original name, ‘Sohra’.

Sohra as it has always been called was pronounced “Cherra” by the British. Located 40 kilometres, North Of Shillong in East Khasi Hills, Sohra eventually evolved into a temporary name, Cherrapunji, which according to many means ‘land of oranges’. But locals say “punji” meaning “a cluster”, was added to “Cherra” by the British-employed Bengali bureaucrats. Another belief is that Cherrapunji’s original name is ‘Sohrapoonjee’. ‘Poonjee’ refers to the head village where the ‘seat of power’ of the Chieftain is. The English who ruled over this place from 1830-1947 could not pronounce ‘Sohrapoonjee’ correctly and named it ‘Cherrapunjee’. Some old colonial period writings refer to it as ‘Chirra’ too. (Sohra Civil Sub-Division). Later the Meghalaya state government renamed Cherrapunji to its original name, ‘Sohra’.

The British were in search of cooler places in their colonies because colder climates were seen as healthier and more familiar environments where tropical diseases were less prevalent. Seeking a place with cool weather and strategic benefits, David Scott, the British East India Company’s first agent to the North East chose the tribal hamlet of Sohra. One of the earliest references to Sohra’s rain is found in a letter written by Scott dated June 10, 1827. Addressed to the then Governor General Lord William Pitt Amherst, the letter read,“We have had almost incessant rains and mist here since the 28th last (May 1827)”. (According to a BBC report by Trishna Mohanty).

The Monsoons

Every year in the monsoon months, from May to September, Meghalaya is drenched by monsoon winds that travel north from the Bay of Bengal across the humid floodplains of Bangladesh. Upon reaching the steep Garo, Khasi, and Jaintia hills of Meghalaya, these air currents are forced through gorges and up steep slopes, where they condense and release their moisture as orographic rainfall. With rains and fogs enveloping this quaint little village, in 1831, on Scott’s recommendation, the British government in India established a hill station in Sohra as their headquarters in North-East India. To them, it also resembled Scotland. That is how, Meghalaya, meaning the land of the clouds, later earned the British sobriquet “the Scotland of the East”.

Every year in the monsoon months, from May to September, Meghalaya is drenched by monsoon winds that travel north from the Bay of Bengal across the humid floodplains of Bangladesh. Upon reaching the steep Garo, Khasi, and Jaintia hills of Meghalaya, these air currents are forced through gorges and up steep slopes, where they condense and release their moisture as orographic rainfall. With rains and fogs enveloping this quaint little village, in 1831, on Scott’s recommendation, the British government in India established a hill station in Sohra as their headquarters in North-East India. To them, it also resembled Scotland. That is how, Meghalaya, meaning the land of the clouds, later earned the British sobriquet “the Scotland of the East”.

Of late, it has been replaced by Mawsynram, situated just 15 KM to the west. During the winter months, however, Sohra faces an acute water shortage. This doesn’t add up for the wettest place to face a water crisis, but in reality, erratic rainfall patterns especially in the dry season (November, December, January and February) are to be blamed, along with the increasing population and irreversible environmental degradation globally.

Of late, it has been replaced by Mawsynram, situated just 15 KM to the west. During the winter months, however, Sohra faces an acute water shortage. This doesn’t add up for the wettest place to face a water crisis, but in reality, erratic rainfall patterns especially in the dry season (November, December, January and February) are to be blamed, along with the increasing population and irreversible environmental degradation globally.

Sohra holds two Guinness World Records for its rainfall. In a single year, between August 1860 and July 1861, Sohra received a staggering 26,471 millimetres (mm) of rainfall, securing its place in history. Additionally, it holds the record for the maximum amount of  rainfall in a single month, with 9,300 millimetres in July 1861. That is how Sohra secured the title of the “Wettest Place on Earth” and it held onto that title for decades. However, after comparing the statistics with Mawsynram from 1970 to 2010, it was found that, on average, Mawsynram receives slightly more rainfall. Mawsynram on average receives about 11,873 mm of rainfall annually while the annual precipitation of Sohra comes in at about 11,777 mm.

rainfall in a single month, with 9,300 millimetres in July 1861. That is how Sohra secured the title of the “Wettest Place on Earth” and it held onto that title for decades. However, after comparing the statistics with Mawsynram from 1970 to 2010, it was found that, on average, Mawsynram receives slightly more rainfall. Mawsynram on average receives about 11,873 mm of rainfall annually while the annual precipitation of Sohra comes in at about 11,777 mm.

Is Sohra drying up?

On June 17, 2022, Mawsynram set a new record by receiving 1003.6 mm in just 24 hours which became its highest single-day record for June. Now that the title remains with Mawsynram, why is Sohra drying up and facing water shortage during the winter months? So much so that the Home Minister of India, Amit Shah launched a plantation drive there in July 2021.

One of the reasons behind the shortage of water during the winter months and the drying up of Sohra is the erratic rainfall during the winter. As the moisture-bearing clouds wane after the retreating monsoons, the amount of rainfall also comes down. The Indian Meteorological Department’s (IMD) data for the last decade reveals a troubling trend. Sohra has been losing an average of 22.58 millimetres of annual rainfall per year. In the winter months, the pattern is even more abnormal. Comparing the data of the dry months (December – February) reveals that January and February see minimal rainfall with an average staying below 70 mm with occasional spikes in February but near-zero rainfall in January. A similar trend is observed in November and December as well. In recent years, in 2020 and 2023 November and December recorded rainfall significantly different from the long-term averages.

One of the reasons behind the shortage of water during the winter months and the drying up of Sohra is the erratic rainfall during the winter. As the moisture-bearing clouds wane after the retreating monsoons, the amount of rainfall also comes down. The Indian Meteorological Department’s (IMD) data for the last decade reveals a troubling trend. Sohra has been losing an average of 22.58 millimetres of annual rainfall per year. In the winter months, the pattern is even more abnormal. Comparing the data of the dry months (December – February) reveals that January and February see minimal rainfall with an average staying below 70 mm with occasional spikes in February but near-zero rainfall in January. A similar trend is observed in November and December as well. In recent years, in 2020 and 2023 November and December recorded rainfall significantly different from the long-term averages.

A similar pattern is getting mirrored in Mawsynram as well. The question beckons,will Mawsynram too lose its “Wettest Place” tag if this goes on?

The problem of water shortage is now not limited to Sohra, but the entire state. Meghalaya, the abode of clouds, almost entirely depends on monsoons for its water supply, power and agriculture. Along with changing patterns in Sohra and Mawsynram, rainfall has seen a significant decline throughout the state, resulting in the depletion of water sources. A report titled “Complex and worrying questions to Meghalaya’s water crisis”, published by the noted scholar Baniateilang Majaw in the “Sustainable Water Resources Management” journal observed a 15% decrease in rainfall over the past five years. The study indicates that the present crisis results from a combination of factors, including climate change, deforestation, and unsustainable water management practices.

The problem of water shortage is now not limited to Sohra, but the entire state. Meghalaya, the abode of clouds, almost entirely depends on monsoons for its water supply, power and agriculture. Along with changing patterns in Sohra and Mawsynram, rainfall has seen a significant decline throughout the state, resulting in the depletion of water sources. A report titled “Complex and worrying questions to Meghalaya’s water crisis”, published by the noted scholar Baniateilang Majaw in the “Sustainable Water Resources Management” journal observed a 15% decrease in rainfall over the past five years. The study indicates that the present crisis results from a combination of factors, including climate change, deforestation, and unsustainable water management practices.

Sohra is not green, the plateau is mostly barren and pastureless. The reason behind the drought in Sohra can be the excessive rainfall during monsoons itself. When a place experiences too much rainfall, the topsoil, rich in manure gets washed off, exposing the subsequent layers to degradation which can’t grow pasture and sustain the plant life. With no trees or reservoirs to hold back the monsoon rains, the rainwater runs off the plateau into Bangladesh. A host of waterfalls rushing downhill are flocked by tourists during the monsoons. By winter, they run dry and so do the local springs.

Sohra is not green, the plateau is mostly barren and pastureless. The reason behind the drought in Sohra can be the excessive rainfall during monsoons itself. When a place experiences too much rainfall, the topsoil, rich in manure gets washed off, exposing the subsequent layers to degradation which can’t grow pasture and sustain the plant life. With no trees or reservoirs to hold back the monsoon rains, the rainwater runs off the plateau into Bangladesh. A host of waterfalls rushing downhill are flocked by tourists during the monsoons. By winter, they run dry and so do the local springs.

Along with that, the population also comes into play. From only 6,097.000 people in 1981, the population has grown to 11,722.000 in 2011 as per the Census Report of India. The region’s water supply system, commissioned more than 20 years ago to cater to a smaller population, now struggles to meet the demands of rapid urbanisation. Especially during dry seasons, people are forced to walk several kilometres to get water from the supply which isn’t free from contamination by bacteria and runoff from the coal mines. The other option is purchasing water from private tankers. Locals are often forced to the latter option even at an inflated price.

Unplanned urban structures in Sohra are taking up areas for seepage of rainwater. When the state became the first in the country to implement a water policy in 2019, it mandated that all buildings must have rooftop rainwater harvesting and groundwater recharge systems, to be enforced by relevant authorities. However many residential constructions have received clearance certificates without proper checks for rainwater harvesting systems.

How does this affect our lives? The number of tourists might have decreased, but domestic tourists from nearby states still flock to Sohra on weekends. Earlier the umbrellas that dotted the streets against the downpour now open for shade from the sun. Elderly locals recall that they wouldn’t see any sunrays for more than a month, but now complain of the heat. The temperature in the area has also climbed up the bars of mercury in recent years. There is a growing threat that both Mawsynram and Sohra (Cherrapunji) might lose the tag of wettest place to Arunachal’s Koloriang which also vies for the same title. In a report published by The Shillong Times on June 26 last year, it was reported that the Indian Meteorological Department (IMD) was going to set up a rain testing centre at one of the rainiest places — Koloriang in Arunachal Pradesh soon, Cherrapunji or Mawsynram might lose the exclusive tag of the ‘wettest place on Earth’.

Koloriang, the hilly district headquarters of Kurung Kumey, is situated at an altitude of 1,000 metres and is dotted by high mountains. Located on the right bank of the Kurung River, a major tributary of the Subansiri River, this town experiences unusual rainfall almost year-round, except during the three peak winter months. Residents of Koloriang have been advocating for its recognition as the wettest place on Earth, aiming to replace the current titleholder, Mawsynram. Securing the title of ‘wettest place on Earth’ would not only boost tourism to the town and the state but also get enlisted in the global tourism map. If this happens, unfortunately, the state might lose a significant number of tourists who come from the plains just to relish the rain.

So where do we go from here? To address Sohra’s water issues and sustain its ecological balance, several steps are necessary. It requires a concerted effort from multiple stakeholders. It necessitates a symbiotic relationship between government agencies, each bringing unique expertise and resources to the table. Simultaneously, it calls for a unified front comprising individuals from diverse backgrounds such as civil society leaders, educators, environmental activists, scientists, and students towards implementing sustainable practices, such as encouraging and enforcing rainwater harvesting and groundwater recharge systems, is crucial.

As parts of the country are reeling from acute heatwave, the other with untimely cyclonic rains, floods and coping with its ravaging consequences, it is time to act!