By Vishnu Makhijani

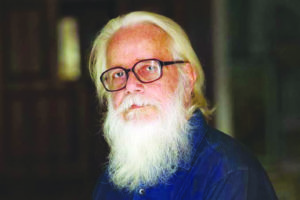

S Nambi Narayanan, the aerospace engineer discharged in what is known as the ISRO spy case of the 1990s, is now playing the martyr to cover up his own role in the case, says veteran

journalist J Rajasekharan Nair in the sequel to his book on the infamous episode.

“Nambi Narayanan was a key figure in the failed operation to illegally transport cryogenic rocket technology from Glavkosmos (a subsidiary of the Russian State Space Corporation Roscomos) to ISRO using clandestine methods under a 1991 agreement between Glavkosmos and ISRO that was cancelled by Russia in 1993 invoking a force majeure,” Nair said in an interview.

“The operation was jointly planned by ISRO top brass and an influential section in Glavkosmos. The operation was illegal because the 1991 agreement meant to transfer the cryogenic technology was cancelled and the new agreement signed in 1994 January had no clause for technology transfer,” Nair said.

Glavkosmos, according to him, agreed to supply the material but was not ready for door-to- door delivery. Nambi Narayanan contacted Air India but it refused to carry the material without proper documents. Nambi Narayanan then contacted Ural Airlines “who agreed to take the risk”.

“Though there are five airports in Moscow (where Glavkosmos is located), airlifting the material from any of these airports, hoodwinking the US eyes, was unthinkable. So the material was transported to Tashkent in Uzbekistan by road travelling more than 3,300 km and from there airlifted to ISRO. It is reliably learnt that Nambi Narayanan was on the first Ural flight,” Nair said.

“Nambi Narayanan doesn’t want these pieces of information (that ISRO had planned an illegal operation and he was a crucial player in it) to become public. Though he had approached different legal forums nearly ten times, never did he pray that the entire matter surrounding the espionage case be proved. Moreover, when a PIL was filed before the Kerala High court for a judicial enquiry into the espionage case, he fought against it.

“He wants only that much truth that would keep him afloat in his safe zone to come to the surface and doesn’t want the whole matter (for instance, who planted the false and baseless spy story and why) to reach the public domain,” Nair maintained.

The ISRO spy case, which hit the headlines in 1994, centred around allegations of transfer of cryogenic technology and confidential documents on India’s space programme to a foreign country by two scientists (including Nambi Narayanan) and four others, including two Maldivian women. Nambi Narayanan was eventually discharged after a laborious process, awarded compensation of Rs 50 lakhs by the Supreme Court but accepted Rs 1 crore as an out-of-court settlement from the Kerala government on a Rs 1 crore suit of damages he had sought, and was awarded a Padma Bhushan in 2019.

“As the public gropes in the dark about the essence of the ISRO espionage case, a re-evaluation of the case is imperative to see afresh why the espionage story cropped up. It is most essential to re-read the text of the ISRO espionage case through documents, facts, and prudence, and not through the projection of individuals as the good, the bad and the ugly,” Nair writes in the book, Classified – Hidden Truths In the ISRO Spy Story (Srishti).

The media, in general, he said during the interview, has not discussed the meat of the matter: What was the espionage case and how could IB and Kerala Police say that certain persons in ISRO had leaked cryogenic technology to a foreign country using two semi-literate Maldivian women at a time (1994) when ISRO didn’t have the technology?

“No journalist bothered to check with ISRO whether they had the cryogenic technology in 1994. Instead, media houses sent journalists to the Maldives to collect information about the two Maldivian women and filed sleazy stories on them. All the accused were presented as morally corrupt persons when morality had nothing to do with the espionage case,” Nair said.

After the CBI had concluded in 1996 that the case was false and baseless, nobody, not even CBI, asked “how the absurd spy story came from nowhere and why the Director of IB had directed the Kerala Police to register a case under the Indian Official Secrets Act”, Nair said

“Nobody, not even the CBI asked why was Ural Airlines carrying material to ISRO from Glavkosmos and why the transportation came to an abrupt end in the wake of the espionage story (if the transportation was legal).

“Nobody (not even the judiciary) asked the pertinent questions how a case could be filed under the Indian Official Secrets Act without ISRO or the central government filing a written complaint as is unambiguously made clear in Section 13(3) and (5) of the Act,” Nair contended.

Instead, Nair said, the media were hailing the police officers who did an illegal act of registering a case under the Indian Official Secrets Act and airing the absurd story that cryogenic rocket technology had been leaked to a foreign country at a time when ISRO didn’t have the technology.

“Now, when the situation changed, the same media are hailing the old villains as the new heroes and the old heroes are the new villains. So, Nambi Narayanan and other accused are the new heroes; the Kerala Police officers and IB officials are villains. Their discussions are around individuals and are not focused on the central matter.

“The espionage case is a techno-legal matter. It was never discussed in that way. It was always discussed from the point of view of persons; not from the POV of facts,” Nair maintained.

“That is why the case is still confusing. My book attempts to do a post mortem of the case from the techno-legal angle strictly based on facts, documents, and records,” he added.

ISRO and the Indian government, Nair writes in the book, “need to tell the people to what extent the misfired ‘patriotic’ adventure has cost ISRO in terms of money, especially when the business from the space market is expected to touch $558 billion by 2026 and up to $1.75 trillion by 2040.

“It is high time ISRO and the government of India come clean on the matter. If both parties confirm this operation (under the 1991 agreement) was in the interest of the nation and hence need to be treated as brave acts of ‘patriotism’, a different picture would emerge.

“But then, one needs to deconstruct the very concept of patriotism,” Nair concludes the book.